User:Diderot/Gothic phonology

This article concerns the phonology and phonetics of the Gothic language.

Phonetic and phonological system

[edit]In order to raise legibility and contrary to the conventional way of transcribing Gothic, this article contains phonological transcriptions between square brackets, which normally are used only for phonetic transcriptions. Because the forward slash is not divisible, they may be displayed on the following line. The macron is used to designate a long vowel, instead of ":".

Gothic underwent only the first consonontal mutation described by Grimm's law and Verner's law. It predates the second mutation characteristic of Old High German.

It is possible to determine more or less exactly how the Gothic of Ulfilas was pronounced, primarily through comparative phonetic reconstruction. Furthermore, because Ulfilas tried to follow the original Greek text as much as possible in his translation, we know that he used the same writing conventions as those of contemporary Greek. Since the Greek of that period is well documented, it is possible to reconstruct much of Gothic pronunciation from his text. In addition, the way in which non-Greek names are transcribed in the Greek Bible and in Uliflas' Bible is very informative.

Vowels

[edit]Simple vowels

[edit]- [a], [i] and [u] can be either long or short. Gothic writing distinguishes between long and short vowels only for [i] - writing i for the short form and ei for the long (a digraph or false diphthong), in imitation of Greek usage. Single vowels are long primarily where a historically present nasal consonant has been dropped in front of an [h] (a case of compensatory lengthening). Thus, the preterite of the verb briggan [briŋgan] (English: "to bring"; German: "bringen") becomes brahta [brāxta] (English: "brought"), from the proto-Germanic *braŋk-ta. In detailed transliteration, where the intent is more phonetic transcription, length is noted by a macron (or failing that, often a circumflex): brāhta, brâhta. [ū] is found often enough in other contexts: brūks ("useful").

- [ē] and [ō] and long and closed. They are written as e and o: neƕ [nēʍ] ("near", cognate to the German nach); fodjan [ɸōdjan] ("to feed").

- [ɛ] and [ɔ] and short and open. They are noted using false diphthongs, like ei for [ī], but also using ai and au: taihun [tɛhun] ("ten"), dauhtar [dɔxtar] (English: "daughter"; German: "Tochter"). In transcribing Gothic, accents are placed on the false diphthongs aí and aú to indicate their true qualities: taíhun, daúhtar. [ɛ] and [ɔ] appear primarily before [r], [h] and [ʍ].

- [y] (pronounced like the ew in new) is a Greek sound used only in borrowed words. It is transcribed as [w] in vowel positions: azwmus [azymus] ("unleavened bread", from the Greek ἄζυμος). It represents an υ (upsilon) or the diphthong οι (omicron + iota) in Greek., both of which were pronounced [y] in period Greek. This letter is often transcribed as [y] and since the Greek sound was not present in Gothic, it was most likely pronounced [i].

- The letter w seems, in those words not borrowed from Greek and not followed by a vowel, to represent an [u]. Why Gothic manuscripts use w as a vowel in place of u is not clear: saggws [saŋgus] ("song").

- For etymological reasons, this list would not be complete without the phonemes [ɛ̄] and [ɔ̄], present only in a few words and always placed before a vowel. In transliteration and transcription alike, they are written as ai and au. This distinguishes them in transcription (but not in transliteration) from ái / aí and áu / aú: waian [wɛ̄an] ("to blow"), bauan [bɔ̄an] ("to build", cognate to German "bauen").

Diphthongs

[edit]- [ai] and [au] are simple enough. However, they are written in the same way as false diphthongs: ains [ains] ("one", German: "eins"), augo [auɣō] ("eye", German: "Auge"). To tell them apart from false diphthongs, the true diphthongs are written as ái and áu: áins, áugo.

- [iu] is a descending diphthong like [ai] and [au]. It is pronounced [iu] and not [iu]: diups [diups] ("deep").

- Greek diphthongs: In Ulfilas' era, all the diphthongs of classical Greek had become simple vowels in speech (monophthongization), except for αυ (alpha + upsilon) and ευ (epsilon + upsilon), which were probably still pronounced as [aβ] et [eβ]. (They evolved into [av] and [ev] in modern Greek.) Ulifas notes them, in words borrowed from Greek, as aw and aiw (the latter transcribed as aíw to avoid confusion with ai, which was pronounced [ɛ]), rendered as [au, ɛu] or as [aw, ɛw] respectively: Pawlus [paulus] ("Paul"), from the Greek Παῦλος, aíwaggelista [ɛwaŋgēlista] ("evangelist"), from the Greek εὐαγγελιστής, via the Latin "evangelista".

- Simple vowels and diphthongs (real or false ones) can be followed by a [w], which was likely pronounced as the second element of a diphthong with roughly the sound of [u]. It seems likely that this more of an instance of phonetic coalescence than of phonological diphthongs (as, for example, the sound [aj] in the French word paille ("straw"), which is not the diphthong [ai] but rather a vowel followed by an approximant): alew [alēu] ("olive oil", derived from the Latin "oleum"), snáiws [snaius] ("snow"), lasiws [lasius] (or possibly [lasijus], [lasjus] or [lasiws]; "tired", cognate to the English "lazy").

Voiced sonorants

[edit]The sonorants [l], [m], [n] and [r] can act as the nucleus of a syllable in Gothic, just as they could in proto-Indo-european and in Sanskrit for [l] and [r]. After the final consonant of a word, these sonorants were pronounced as vowels. This is also the case in modern English: for example, "bottle" is pronounced [bɒtl̩] in many dialects. Some Gothic examples: tagl [ta.ɣl̩] ("hair", cognate to "tail"), máiþms [mai.θm̩s] ("gift"), táikns [tai.kn̩s] ("sign", cognate to the English word "token" or German "Zeichen") et tagr [taɣr̩] ("tear", as in crying).

Consonants

[edit]In general, Gothic consonants are devoiced at the ends of words. Gothic is rich in fricative consonants (although many of them may have been approximants, it's hard to separate the two) derived by the processes described in Grimm's law and Verner's law and characteristic of Germanic languages. Gothic is unusual among Germanic languages in having a [z] phoneme which is not derived from an [r] through rhotacization. Furthermore, the doubling of written consonants between vowels suggests that Gothic made distinctions between long and short, or geminated consonants: atta [atːa] ("papa"; a diminutive comparable to the Greek ἄττα and latin "atta", with the same meaning), kunnan [kunːan] ("to know", German: "kennen").

Occlusives

[edit]- [p], [t] and [k] are regularly noted by p, t and k respectively: paska [paska] ("Easter", from the Greek πάσχα), tuggo [tuŋgō] ("tongue"), kalbo [kalbō] ("calf").

- [kw] is a complex occlusive followed by a labio-velar approximant, comparable to the Latin qu. It is transliterated as q: qiman [kwiman] ("to come"). It is etymologically derived from the proto-Indo-European consonant *gw.

- [b], [d] and [g]: Except between vowels, the consonants marked by the letters b, d and g in the Gothic alphabet are voiced occulsives. When they are next to a devoiced consonant, they are most likely also devoiced: blinds [blind̥s] ("blind"), dags [dag̊s] ("day", Dutch: "dag"), gras [gras] ("grass"). At the ends of words, [b] and [d] were probably devoiced, although it is possible that they were changed into [ɸ] and [θ] respectively: lamb [lamp] ("lamb"), band [bant] ("he/she ties", cognate to English "bound").

Fricatives

[edit]- [s] and [z] are usually written s and z, but [z] is never at the end of a word: saíhs [sɛxs] ("six", compare to German "sechs"), aqizi [akwizi] ("axe").

- [ɸ] and [θ] transcribed as f and þ, correspond directly to the phonemes [p] and [t]. It is likely that the relatively unstable sound [ɸ] became [f]. f and þ are also derived from b and d at the ends of words, when they are devoices and become approximants: gif [giɸ] ("give" in the imperative, from giban), miþ [miθ] ("with", cognate to the Old English "mid" and the German "mit").

- [x] (in German philology, usually transcribed as χ) is written is a number of different ways:

- As an approximant form of [k], it is written as h before consonants or at the ends of words: nahts [naxts] ("night"), jah [jax] ("and", cognate to the Greek ὅς "who" and the German "ja" ("yes"), from the Indo-European *yo-s).

- If it is derived from a [g] at the end of a word, it is written g: dag [dax] ("sky" in the accusative case).

- In some borrowed Greek words, it is written x and represents the Greek letter χ (khi): Xristus [xristus] ("Chris", from the Greek Χριστός). It may also have signified a [k].

- [h] is written as h and is only found at the beginning of words or between vowels. [h] is an allophone of [x]: haban ("to have", German "haben"), ahtáutehund [axtautēhunt] ("eleven").

- [β], [ð] and [ɣ] are voiced fricatives only found between vowels. They are allophones of [b], [d] and [g] and are not distinguished from them in writing. [β] may have become [v], a more stable labiodental form (a case of fortition). In Germanic language phonetics, these phonemes are usually transcribed as ƀ, đ and ǥ respectively: haban [haβan] ("to have"), þiuda [θiuða] ("people", cognate to German "Deutsch", English "Dutch", Dutch "Diets", Italian "tedesco"), áugo [auɣō] ("eye", German "Auge").

- [xw] is a labiovelar variant of [x], derived from the proto-Indo-European *kw. It probably was pronounced as [ʍ] (a voiceless [w]) as it did in many dialects of English, where it is always written as wh. It is transliterated as the ligature ƕ: ƕan [ʍan] ("when"), ƕar [ʍar] ("where"), ƕeits [ʍīts] ("white").

Nasal consonants

[edit]Nasals in Gothic, like most languages, are pronounced at the same point of articulation of either the consonant that precedes them or that follows them. (The technical term is assimilation.) Therefore, clusters like [md] and [nb] are not possible. Gothic has three nasal consonants, of which one is an allophone of the others, found only in complementary distribution with them.

- [n] and [m] are freely distributed - they can be found in any position in and form minimal pairs - except for certain contexts where they are neutralized: [n] before a bilabial consonant becomes [m], while and [m] preceding a dental stop becomes an [n], as per the principle of assimilation described in the previous paragraph. In front of a velar stop, they both become [ŋ]. [n] and [m] are transcribed as n and m, and in writing neutralisation is marked: sniumundo [sniumundō] ("quickly").

- [ŋ] is not a phoneme and cannot appear freely in Gothic. It is present where a nasal consonant is neutralised before a velar stop and is in a complementary distribution with [n] and [m]. Following Greek conventions, it is written as g when it is in front of a velar consonant: þagkjan [θaŋkjan] ("to think"), sigqan [siŋkwan] ("to sink"). The cluster ggw, however, notes a geminated [g] followed by [w]: triggws [triggus] ("true"). Sometimes, n placed before a velar consonant must be interpreted as [ŋ]: þankeiþ instead of þagkeiþ [θaŋkīθ] ("he thinks").

Approximants and other phonemes

[edit]- [w] is transcribed as w before a vowel: weits [wīts] ("while"), twái [twai] ("two", compare to German "zwei").

- [j] is written as j: jer [jēr] ("year"), sakjo [sakjō] ("woman")

- [l] is used much as in English and other European languages: laggs [laŋg̊s] ("long"), mel [mēl] ("hour"). Remember that this same letter can signify the voiced approximant [l̩].

- [r] is a trilled [r] or a flap [ɾ]. There is no clear way to distinguish the two in transcription: raíhts [rɛxts] ("right"), afar [aɸar] ("after"). The same letter can signify the voiced approximant [r̩].

Schematic Tables

[edit]These tables use IPA notation.

Vowels

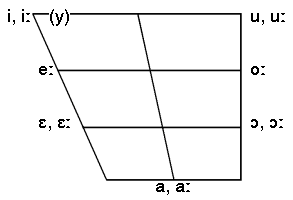

[edit]Simples

|

Diphtongues

|

Consonants

[edit]Stress and Intonation

[edit]Stress in Gothic can be reconstructed through phonetic comparison, Grimm's law and Verner's law. Gothic used a tonic accent rather than a stress accent, in contrast to proto-Indo-European and many later Indo-European languages like Sanskrit and Classical Greek. The features of Gothic accents can be seen primarily in the origin of some of its long vowels (like [ī], [ū] et [ē]) and through a study of syncopes (the loss of unstressed vowels). The stress accent of Indo-European was completely replaced by a tonic accent and changed in the process: Just like other Germanic languages, the accent falls on the first syllable. (For example, in modern English, nearly all words that do not have accents on the first syllable are borrowed from other languages.) Accents do not shift when words are inflected. In most compound words, the location of the stress depends on its placement in the second part:

- In compounds where the second word is a noun, the accent is on the first syllable of the compound.

- In compounds where the second word is a verb, the accent falls on the first syllable of the verbal component. Elements prefixed to verbs are otherwise atonic, except in the context of separable words (words that can be broken in two parts and separated in regular usage, for example, separable verbs in German and Dutch) - in those cases, the prefix is tonic.

Examples: (with comparable words form modern Germanic languages)

- Non-compound words: marka ['marka] ("border", "borderlands"; cognate to "march" as in the Spanish Marches); aftra ['aɸtra] ("after"); bidjan ['bidjan] ("pray", cognate to modern German "bitten").

- Compound words:

- Noun second element: guda-láus ['guðalaus] ("godless"),

- Verb second element: ga-láubjan [ga'laubjan] ("believe", cognate to modern German "glauben", from Old High German g(i)louben by syncope of the atonic i).

Back to Gothic language.