1753 in science

Appearance

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| +... |

| 1753 in science |

|---|

| Fields |

| Technology |

| Social sciences |

| Paleontology |

| Extraterrestrial environment |

| Terrestrial environment |

| Other/related |

The year 1753 in science and technology involved some significant events.

Astronomy

[edit]- Ruđer Bošković's De lunae atmosphaera demonstrates the lack of atmosphere on the Moon.[1]

Botany

[edit]

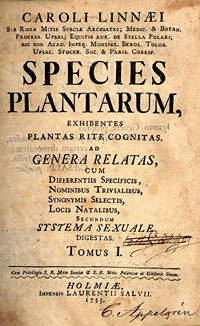

- May 1 – Publication of Linnaeus' Species Plantarum, the start of formal scientific classification of plants.[2]

- June – Establishment in Florence of the Accademia dei Georgofili, the world's oldest society devoted to agronomy and scientific agriculture.

Chemistry

[edit]Computer science

[edit]- January 1 – Retrospectively, the minimum date value for a datetime field in an SQL Server (up to version 2005) due to this being the first full year since Britain's adoption of the Gregorian calendar.

Medicine

[edit]- James Lind publishes the first edition of A Treatise on the Scurvy (although it is little noticed at this time).[6]

Physics

[edit]- November 25 – The Russian Academy of Sciences announces a competition among chemists and physicists to provide "the best explanation of the true causes of electricity including their theory"; the prize will be won in 1755 by Johann Euler.[7]

Technology

[edit]- February 17 – The concept of electrical telegraphy is first published in the form of a letter from 'C. M.' to The Scots' Magazine.[8]

- Benjamin Franklin invents the lightning rod, to ring a bell when struck by lightning, following his 1752 kite and key tests.

- George Semple uses hydraulic lime cement in rebuilding Essex Bridge in Dublin.[9]

Awards

[edit]Births

[edit]- March 26 – Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, Anglo-American physicist (died 1814)

- April 28 – Franz Karl Achard, chemist (died 1821)

- August 3 – Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, British statesman and scientist (died 1816)

Deaths

[edit]- August 6 – Georg Wilhelm Richmann, Russian physicist, electrocuted (born 1711)

- December – Thomas Melvill, Scottish natural philosopher (born 1726)

References

[edit]- ^ Энциклопедия для детей (астрономия). Москва: Аванта+. 1998. ISBN 978-5-89501-016-7.

- ^ Date adopted by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.

- ^ Geoffroy, C. F. (1753). "Sur Bismuth". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences: 190. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements. II. Elements known to the alchemists". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 11. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9...11W. doi:10.1021/ed009p11.

- ^ Hammond, C. R. (2004). "The Elements". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4-1. ISBN 0-8493-0485-7.

- ^ Bartholemew, M. (January 2002). "James Lind and Scurvy: a revaluation". Journal for Maritime Research. 4. National Maritime Museum: 1–14. doi:10.1080/21533369.2002.9668317. S2CID 42109340.

- ^ Juznic, Stanislav Joze (2012). "Hallerstein and Gruber's Scientific Heritage". The Circulation of Science and Technology: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference of the European Society for the History of Science. Societat Catalana d'Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica. p. 358.

- ^ "An Expeditious Method of Conveying Intelligence". Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003). The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 48.

- ^ Semple, George (1776). A Treatise on Building in Water. Dublin: Husband.

- ^ "Copley Medal | British scientific award". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 July 2020.