Axeman of New Orleans

The Axeman of New Orleans | |

|---|---|

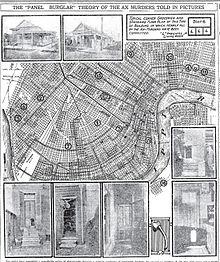

Illustrated map of scenes of the Axe murders, March 1919 | |

| Criminal status | Never caught |

| Details | |

| Victims | 6 dead, 6 injured |

Span of crimes | May 23, 1918 – October 27, 1919 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Louisiana |

The Axeman of New Orleans was an unidentified American serial killer who was active in and around New Orleans, Louisiana, between May 1918 and October 1919. Press reports during the height of public panic over the killings mentioned similar crimes as early as 1911, but recent researchers have called these reports into question.[1] The attacker was never identified, and the murders remain unsolved.

Background

[edit]As the killer's epithet implies, the victims usually were attacked with an axe, which often belonged to the victims themselves.[2] In most cases, a panel on the backdoor of a home was removed by a chisel, which, along with the panel, was left on the floor near the door. The intruder then attacked one or more of the inhabitants with either an axe or a straight razor. The crimes were not motivated by robbery, and the perpetrator never removed items from his victims' homes.[3]

The majority of the Axeman's victims were Italian immigrants or Italian-Americans, leading many to believe that the crimes were ethnically motivated. Many media outlets sensationalized this aspect of the crimes, even suggesting Mafia involvement despite lack of evidence. Some crime analysts have suggested that the killings were sexually motivated, and that the murderer was perhaps a sexual sadist specifically seeking female victims. Criminologists Colin and Damon Wilson hypothesize that the Axeman killed male victims only when they obstructed his attempts to murder women, supported by cases in which the woman of the household was murdered but not the man.

A less plausible theory is that the Axeman committed the murders in an attempt to promote jazz music, suggested by written correspondence attributed to the killer in which he stated that he would spare the lives of those who played jazz in their homes.[4] On March 13, 1919, a letter purporting to be from the Axeman was published in newspapers, saying that he would kill again at fifteen minutes past midnight on the night of March 19 but would spare the occupants of any place where a jazz band was playing. That night all of the city's dance halls were filled to capacity, and professional and amateur bands played jazz at parties at hundreds of houses around town. There were no murders that night.[5]

Hell, March 13, 1919

Esteemed Mortal:

They have never caught me and they never will. They have never seen me, for I am invisible, even as the ether that surrounds your earth. I am not a human being, but a spirit and a demon from the hottest hell. I am what you Orleanians and your foolish police call the Axeman.

When I see fit, I shall come and claim other victims. I alone know whom they shall be. I shall leave no clue except my bloody axe, besmeared with blood and brains of he whom I have sent below to keep me company.

If you wish you may tell the police to be careful not to rile me. Of course, I am a reasonable spirit. I take no offense at the way they have conducted their investigations in the past. In fact, they have been so utterly stupid as to not only amuse me, but His Satanic Majesty, Francis Josef, etc. But tell them to beware. Let them not try to discover what I am, for it were better that they were never born than to incur the wrath of the Axeman. I don't think there is any need of such a warning, for I feel sure the police will always dodge me, as they have in the past. They are wise and know how to keep away from all harm.

Undoubtedly, you Orleanians think of me as a most horrible murderer, which I am, but I could be much worse if I wanted to. If I wished, I could pay a visit to your city every night. At will I could slay thousands of your best citizens, for I am in close relationship with the Angel of Death.

Now, to be exact, at 12:15 (earthly time) on next Tuesday night, I am going to pass over New Orleans. In my infinite mercy, I am going to make a little proposition to you people. Here it is: I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have just mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it out on that specific Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.

Well, as I am cold and crave the warmth of my native Tartarus, and it is about time I leave your earthly home, I will cease my discourse. Hoping that thou wilt publish this, that it may go well with thee, I have been, am and will be the worst spirit that ever existed either in fact or realm of fantasy.

-The Axeman

The Axeman was never caught or identified, and his crime spree stopped as mysteriously as it had started. The murderer's identity remains unknown, although various possible identifications of varying plausibility have been proposed.

Suspects

[edit]

Crime writer Colin Wilson speculates the Axeman could have been Joseph Monfre, a man shot to death in Los Angeles in December 1920 by the widow of Mike Pepitone, the Axeman's last known victim. Wilson's theory has been widely repeated in other true crime books and websites. However, true crime writer Michael Newton searched public, police and court records in New Orleans and Los Angeles, as well as newspaper archives, and failed to find any evidence of a man named "Joseph Monfre" (or a similar name) having been assaulted or killed in Los Angeles.[6]

Newton was also not able to find any information that Mrs. Pepitone (identified in some sources as Esther Albano, and in others simply as a "woman who claimed to be Pepitone's widow") was arrested, tried or convicted for such a crime, or indeed had been in California. Newton notes that "Momfre" was not an unusual surname in New Orleans at the time of the crimes. It appears that there actually may have been an individual named Joseph Momfre or Mumfre in New Orleans who had a criminal history, and who may have been connected with organized crime; however, local records for the period are not extensive enough to allow confirmation of this, or to positively identify the individual. Wilson's explanation is an urban legend, and there is no more evidence now on the identity of the killer than there was at the time of the crimes.[6]

Two of the alleged "early" victims of the Axeman, an Italian couple named Schiambra, were shot by an intruder in their Lower Ninth Ward home during the early morning hours of May 16, 1912. The male Schiambra survived while his wife did not. In newspaper accounts, the prime suspect was referred to by the name of "Momfre" more than once. While radically different than the Axeman's usual modus operandi, if Joseph Momfre was indeed the Axeman, the Schiambras may well have been early victims of the future serial killer.[4]

According to scholar Richard Warner,[7] the chief suspect in the crimes was Frank "Doc" Mumphrey (1875–1921), who used the alias Leon Joseph Monfre/Manfre. Mumphrey's Garden District jazz business, previously struggling, was noted by many in the community as seeming to do unusually good business once the city was compelled by threat of violence to hire jazz bands and play jazz records.

Canonical victims

[edit]Joseph and Catherine Maggio

[edit]On May 23, 1918, Joseph Maggio, an Italian grocer, and his wife Catherine were attacked while sleeping inside their apartment on the corner of Upperline and Magnolia Streets. The killer broke into the residence and cut the couple's throats with a straight razor; Catherine's throat was cut so deeply that her head was nearly severed from her shoulders.[8] The killer then struck both victims with an axe, perhaps in order to conceal the cause of death. Joseph survived the attack, but died minutes after being discovered by his brothers, Jake and Andrew. The killer wrote a message on the nearby pavement reading, "Mrs. Maggio will sit up tonight just like Mrs. Toney", theorized to be a reference to Anthony and Joanna Sciambra, Italian greengrocers who were attacked (Johanna fatally) in 1911.[9]

Police found the bloody clothes of the murderer in the apartment, as he had obviously changed into a clean set of clothes before fleeing the scene. A complete search of the premises was not performed after the bodies were removed, yet the bloodstained razor was later found on the lawn of a neighboring property.[10] Police ruled out robbery as motivation for the attacks, as money and valuables left in plain sight were not stolen by the intruder.[11] The razor was found to belong to Joseph's brother Andrew, who owned a barber shop on Camp Street. His employee, Esteban Torres, told police that Andrew had removed the razor from his shop two days prior to the murder, explaining that he had wanted to have a nick honed from the blade.[8] Andrew, who lived in an adjoining apartment, reported hearing groaning noises through the wall on the night of the murders. Andrew blamed his failure to hear any noise related to the attack itself on his intoxicated state; police, however, were nonetheless surprised that he failed to hear the intruder's forced entry into the home.[12]

Andrew became the police chief's prime suspect in the crime, yet was released after investigators were unable to break down his statement, as well as his account of an unknown man who was supposedly seen lurking near the apartment prior to the murders.[13]

Louis Besumer and Harriet Lowe

[edit]During the early morning hours of June 27, 1918, Louis Besumer and his mistress Harriet Lowe were attacked in private quarters at the back of Besumer's grocery, located at the corner of Dorgenois and Laharpe Streets. Besumer was struck with a hatchet above his right temple, which resulted in a possible skull fracture. Lowe was hacked over the left ear and left with one side of her face permanently paralyzed.[14] The couple were discovered the following morning, alive but critically injured, by bakery wagon driver John Zanca, who had come to the grocery to make a routine delivery.[15] The axe, which had belonged to Besumer himself, was found in an adjacent bathroom.

Besumer stated to investigators that he had been sleeping when he was attacked with the hatchet.[16] Almost immediately, police arrested Lewis Oubicon, a 41-year-old African American man who had been employed in the grocery just a week before the attacks. No evidence existed which could have proved Oubicon guilty, yet police arrested him nonetheless, stating that he had offered conflicting accounts of his whereabouts on the morning of the attack. Oubicon was later released, however, as police were unable to gather sufficient evidence to hold him. Lowe recalled her assailant having been a mulatto man, yet her statement was discounted by police due to her disoriented state. Robbery was said to be the only possible explanation for the attacks, yet no money or valuables were removed from the scene.[15]

Lowe became the center of a media circus as she continually made scandalous and often false statements relating to both the attacks and the character of Besumer. After Besumer fell under suspicion of espionage following the discovery of foreign-written letters in his possession, Lowe told police that she thought he was a German spy, resulting in his immediate arrest; he was released two days later. In August 1918, Besumer was arrested again after Lowe, by then on her deathbed following failed surgery, named him as her assailant. Besumer was charged with murder, and served nine months in prison, before being acquitted on May 1, 1919, after a ten-minute jury deliberation.[16]

Anna Schneider

[edit]During the early morning hours of August 5, 1918, 28-year-old Anna Schneider, who was eight months pregnant, awoke to find a dark figure standing over her and was bashed in the face repeatedly; her scalp was cut open, and her face was covered in blood. Anna was discovered after midnight by her husband, Ed Schneider, as he returned late from work.[17] Anna claimed that she remembered nothing of the attack and gave birth to a healthy baby girl two days later. Ed told police that nothing was stolen from the home besides six or seven dollars that had been in his wallet. The windows and doors of the couple's apartment appeared to have not been forced open, and authorities came to the conclusion that the woman was most likely attacked with a lamp that had been on a nearby table.

James Gleason, who police said was an ex-convict, was arrested shortly after Anna was found. He was later released due to lack of evidence. Lead investigators began to publicly speculate that the attack was related to the previous incidents Besumer and Maggio incidents.[18]

Joseph Romano

[edit]On August 10, 1918, Pauline and Mary Bruno awoke to the sound of a commotion in the adjoining room where their elderly uncle, Joseph Romano, resided. Upon entering the room, the sisters discovered Romano had taken a serious blow to his head, which resulted in two open cuts. The assailant was fleeing the scene as they arrived, yet the girls were able to distinguish that he was a dark-skinned, heavy-set man who wore a dark suit and slouched hat. Romano was able to walk to the ambulance once it arrived yet died two days later due to severe head trauma. His home had been ransacked, yet no items were stolen. Authorities found a bloody axe in the backyard and discovered that a panel on the backdoor had been chiseled away.

The murder created a state of extreme chaos in New Orleans, with residents living in constant fear of an Axeman attack. Police received a slew of reports in which citizens claimed to have seen the killer lurking in local neighborhoods. A few men even called to report that they had found axes in their backyards.[16] John Dantonio, a then-retired Italian detective, made public statements in which he hypothesized that the man who had committed the recent murders was the same who had killed several individuals in 1911. Dantonio described the potential killer as an individual of dual personalities, who killed without motive. This type of individual, Dantonio stated, could very likely have been a normal, law-abiding citizen, who was often overcome by an overwhelming desire to kill. He later went on to describe the killer as a real-life "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde".[19]

Cortimiglia family

[edit]On the night of March 10, 1919, Italian immigrant Charles Cortimiglia and his family – wife Rosie and infant daughter Mary – were attacked in their residence on the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Second Street in Gretna, Louisiana, a New Orleans suburb. Upon hearing screams from the Cortimiglia residence, grocer Iorlando Jordano rushed across the street to investigate. He discovered that Cortimiglia's family had all been attacked by the Axeman. Charles and Rosie had both suffered skull fractures from blows caused by an axe, which was found on their back porch; Mary was killed in her mother's arms from a blow to the back of the neck. Nothing was stolen from the house, but a panel on the backdoor had been chiseled away. Charles was released two days after the attack while his wife remained in the care of doctors.

Upon gaining full consciousness, Rosie made claims that Jordano and his 18-year-old son, Frank, were responsible for the attacks. Iorlando, a 69-year-old man, was in too poor of health to have done so. Frank, more than six feet tall and weighing over 200 pounds, would have been too large to have fit through the panel on the backdoor. Charles vehemently denied his wife's claims, yet police nonetheless arrested the Jordanos and charged them with the murder. The men would later be found guilty. Frank was sentenced to hang, and his father to life in prison. Charles divorced his wife after the trial. Almost a year later, Rosie admitted that she had falsely accused the Jordanos out of jealousy and spite, resulting in their release.[20]

Steve Boca

[edit]On August 10, 1919, grocer Steve Boca was attacked as he slept in his bedroom by an axe-wielding intruder. Boca awoke during the night to find a dark figure looming over his bed. Upon regaining consciousness, Boca ran to the street to investigate the intrusion, and found that his head had been cracked open. The grocer ran to the home of his neighbor, Frank Genusa, where he lost consciousness and collapsed. Nothing had been taken from the home yet, once again, a panel on the backdoor of the home had been chiseled away. Boca recovered from his injuries but could not remember any details of the attack. This attack took place after the emergence of the infamous Axeman letter.[21]

Sarah Laumann

[edit]On the night of September 3, 1919, Sarah Laumann was attacked in her apartment. Neighbors came to check on the young woman, who had lived alone, and broke into the home when Laumann did not answer. They discovered the 19-year-old lying unconscious on her bed, suffering from a severe head injury and missing several teeth. The intruder had entered the apartment through an open window and attacked Laumann with a blunt object. A bloody axe was discovered on the front lawn of the building. Laumann recovered from her injuries yet couldn't recall any details from the attack.[21]

Mike Pepitone

[edit]On the night of October 27, 1919, the wife of Mike Pepitone was awakened by a noise and arrived at the door of her husband's bedroom just as a large, axe-wielding man was fleeing the scene. Pepitone had been struck in the head and was covered in his own blood. Blood spatter covered the majority of the room, including a painting of the Virgin Mary. Pepitone's wife, the mother of six children, was unable to describe any characteristics of the killer other than "large". The Pepitone murder was the last of the alleged Axeman attacks.[21]

In popular culture

[edit]This section contains a list of miscellaneous information. (June 2023) |

- In 1919, local tune writer Joseph John Davilla wrote the song, "The Mysterious Axman's Jazz (Don't Scare Me Papa)". Published by New Orleans–based World's Music Publishing Company, the cover depicted a family playing music with frightened looks on their faces.[22]

- The Australian rock band Beasts of Bourbon released an album in 1984 called The Axeman's Jazz.

- Writer Julie Smith used a fictionalized version of the Axeman events in her 1991 novel The Axeman's Jazz.

- The Axeman killings are also referred to in the short story "Mussolini and the Axeman's Jazz" by Poppy Z. Brite, published in 1997.

- In Chuck Palahniuk's 2005 novel Haunted, the Axeman is mentioned in Sister Vigilante's short story.

- A sentence from the Axeman's letter to The Times-Picayune is spoken at the beginning of Fila Brazillia's song "Tunstall and Californian Haddock."

- Christopher Farnsworth's 2012 novel Red, White, and Blood centers on a murderous spirit called the Boogeyman, which has inhabited numerous bodies throughout history, including the Axeman of New Orleans.[23]

- Ray Celestin's 2014 novel The Axeman's Jazz is a fictionalized version of the Axeman of New Orleans's case.[24]

- The Axeman is mentioned in Season 3, Episode 5 and Season 4, Episode 6 of The Originals.

- My Favorite Murder, a true crime podcast, covered the story of the Axeman on their 60th episode entitled "Jazz It".[25]

- Last Podcast on the Left covered the Axeman as part of their first episode on unsolved serial murders, titled "Unsolved Serial Murders Part 1: The Phantom, the Axe, and the Torso".[26]

- Stuff You Missed In History Class did a two-part miniseries on the Axeman in which they toyed with the idea of his murderous acts having begun prior to 1918.[27]

- Unsolved Murders, a true crime podcast, did a three-part miniseries on the Axeman of New Orleans, ending with their opinions of who the hosts think were responsible.[28]

- On the 13th Eisregen released the song "Axtmann", who tells of the crime.[29]

- BuzzFeed Unsolved, a YouTube series that delves into unsolved true crime cases and the supernatural, explored stories and theories regarding the Axeman in S2E1, "The Terrifying Axeman of New Orleans".[30]

- Alan G. Gauthreaux, author and historian, presented a comprehensive profile of the Axeman Murders in his book, Italian Louisiana: History, Heritage, and Tradition, published in 2014.[31]

- Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, a news satire program, mentioned The Axeman on episode 13 of season 6, titled "Medical Devices." John Oliver gave a brief history of the Axeman after showing a DePuy sales team celebrating their successful numbers for a hip device, which would later be recalled. The celebration was Mardi Gras themed, and included a man dressed up as The Axeman.[32]

- The American swing revival band Squirrel Nut Zippers released a song called "Axeman Jazz (Don't Scare Me Papa)" on their 2018 album, Beasts of Burgundy.[33]

- In the virtual reality game The Walking Dead: Saints and Sinners multiple references to the Axeman can be found. A character references him in dialogue, and a special axe can be found in a safe with the phrase "the Axeman cometh" on the side. There is a reference to him liking jazz, as well as his famous quote from the infamous Axeman's Letter which is used to describe the special axe that can be found, known as the Esteemed Mortal. The Axeman's first physical appearance in game was "The Walking Dead: Saints & Sinners – Chapter 2: Retribution"

- The Axeman, portrayed by Danny Huston, was featured in the third season of American Horror Story, ”Coven” titled 'the Axeman Cometh', which aired November 13, 2013. [34]

- The Axeman is one of three serial killers referenced by Jughead Jones in the opening narration of the fourth episode, "Chapter Seventeen: The Town That Dreaded Sundown", of the second season of Riverdale.

- In 2014 Ray Celestin's The Axeman's Jazz was published, winning the CWA New Blood Dagger for the best debut crime novel of the year.[35]

See also

[edit]- Clementine Barnabet, early 20th century Louisiana voodoo priestess and axe murderer.[36]

- Shotgun Man

- List of serial killers in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Katz 2010, p. 55

- ^ Gibson 2006, pp. 15–16

- ^ Gibson 2006, p. 21

- ^ a b Gibson 2006, p. 20

- ^ Katz 2010, p. 59

- ^ a b Newton 2004, p. 340

- ^ "Fresh light on the axeman of New Orleans". A Fortean in the Archives. July 10, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "Brother's Razor Involves Him in Double Killing". Times-Picayune. May 24, 1918. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ^ "The Axeman of New Orleans". Crime and Investigation. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ "Bloody Clothes Found on Scene of Maggio Crime". Times-Picayune. May 23, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Gibson 2006, p. 18

- ^ Katz 2010, p. 54

- ^ "Andrew Maggio Released; Says He is Innocent". Times-Picayune. May 27, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ "Mrs. Lowe Removed to Besemer Home". Times-Picayune. July 15, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Another Hatchet Mystery; Man and Wife Near Death". Times-Picayune. July 6, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c Katz 2010, p. 56

- ^ Katz 2010, p. 57

- ^ "Police Believe Ax-Man May be Active in the City". Times-Picayune. August 6, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ "Is the Axe-Man Type of Jekyl-Hyde Concept?". Times-Picayune. August 13, 1918. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Katz 2010, p. 58

- ^ a b c Katz 2010, p. 61

- ^ "THNOC Online Catalog". hnoc.minisisinc.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Book Review: Red, White, and Blood by Christopher Farnsworth". Seattle pi. April 27, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ González Cueto, Irene (September 7, 2016). "Tocad, si queréis vivir: Jazz para el asesino del hacha - Cultural Resuena". Cultural Resuena (in European Spanish). Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ "My Favorite Murder". iTunes.

- ^ "Last Podcast On The Left". Simplecast.

- ^ "Stuff You Missed In History Class". Stuff You Missed In History Class.

- ^ "Unsolved Murders: True Crime Stories". Parcast. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Staub, Pascal. "EISREGEN - Fegefeuer | Review bei Stormbringer". www.stormbringer.at (in German). Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ BuzzFeed Multiplayer (July 28, 2017), The Terrifying Axeman of New Orleans, archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved April 23, 2019

- ^ Italian Louisiana: History, Heritage & Tradition ISBN 978-1-625-84915-1

- ^ LastWeekTonight (June 2, 2019), Medical Devices: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO), archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved June 12, 2019

- ^ AllMusic (March 23, 2018), Squirrel Nut Zippers Axeman Jazz, retrieved December 9, 2019

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ The Axeman Cometh (American Horror Story), November 13, 2013

- ^ https://www.waterstones.com/book/the-axemans-jazz/ray-celestin/9781529065633 [bare URL]

- ^ Gauthreaux, Alan G.; Hippensteel, D. G. (November 16, 2015). Dark Bayou: Infamous Louisiana Homicides. McFarland. ISBN 9781476662954.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gibson, Cameron (2006). Serial Murder and Media Circuses. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0275990648.

- Katz, Hélèna (2010). Cold Cases: Famous Unsolved Mysteries, Crimes, and Disappearances in America. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313376924.

- Newton, Michael (August 2004). The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes (Facts on File Crime Library). Facts on File. ISBN 0816049807.

- Davis, Miriam C. (2017). The Axeman of New Orleans. Chicago Review Press Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-61374-871-8.

- The Axman Came from Hell ISBN 1589808983

External links

[edit]- 1918 crimes in the United States

- 1918 in Louisiana

- 1919 crimes in the United States

- 1919 in Louisiana

- 20th century in New Orleans

- American murderers of children

- Axe murder

- History of Louisiana

- Mass stabbings in the United States

- Murder in Louisiana

- People from New Orleans

- Serial killers from Louisiana

- Unidentified American serial killers

- Unsolved murders in the United States