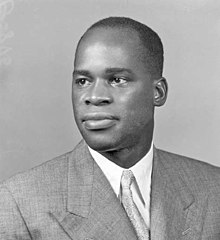

Eduardo Mondlane

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

Eduardo Mondlane | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairman of the Mozambique Liberation Front | |

| In office September 1962 – 3 February 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Samora Machel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane 20 June 1920 Nwajahani, Mandlakazi, Portuguese Mozambique |

| Died | 3 February 1969 (aged 48)[1] Dar es Salaam, Tanzania |

| Political party | Mozambican Liberation Front |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | |

| Profession | Anthropologist |

Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (20 June 1920 – 3 February 1969) was a Mozambican revolutionary and anthropologist, and founder of the Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO). He served as the FRELIMO's first leader until his assassination in 1969 in Tanzania. An anthropologist by profession, Mondlane also worked as a history and sociology professor at Syracuse University before returning to Mozambique in 1963.[2][3]

Early life

[edit]The fourth of 16 sons of a chief of the Bantu-speaking Tsonga, Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane was born in N'wajahani, district of Mandlakazi in the province of Gaza,[4] in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) in 1920. He worked as a shepherd until the age of 12.

He attended several different primary schools before enrolling in a Swiss–Presbyterian school near Manjacaze. He ended his secondary education in the same organisation's church school at Lemana College at Njhakanjhaka Village above Elim Hospital in the Transvaal (Limpopo Province), South Africa. He then spent one year at the Jan H. Hofmeyr School of Social Work before enrolling in Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg but was expelled from South Africa after only a year, in 1949, following the rise of the Apartheid government.

In June 1950, Mondlane attended the University of Lisbon, in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. On Mondlane's request, he was transferred to the United States, where he attended Oberlin College in Ohio at the age of 31, under a Phelps Stokes scholarship. Mondlane enrolled at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, in 1951, starting as a junior, and in 1953 he obtained a degree in anthropology and sociology. He continued his studies at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Mondlane earned an MA (1955), and then a PhD (1960) under the supervision of Melville J. Herskovits on the subject of "Role conflict, reference group, and race".

In 1956, he married Janet Rae Johnson, a white American woman from Indiana whom he met at a Methodist Youth conference."[5]

Anthropology career

[edit]Mondlane began working in 1957 as research officer in the Trusteeship Department of the United Nations which enabled him to travel to Africa and work on a PhD dissertation at Northwestern University.[6] His dissertation, under Herskovits' supervision, focused on the "liberal" tradition of Franz Boas.[7]

He concluded his PhD in 1960 and resigned from his United Nations position in 1961 to be allowed to participate in political activism. He took up a teaching position at Syracuse University that same year where he helped develop the East African Studies Program. In 1963, he resigned from his post at Syracuse to move to Tanzania to engage in the liberation struggle of Frelimo, the presidency of which he won in June 1962.[citation needed]

Political activism

[edit]After graduation, Eduardo Mondlane became a United Nations official. One of António de Oliveira Salazar's most important advisers, Adriano Moreira, a political science professor who had been appointed to the post of Portugal's Minister of the Overseas (Ministro do Ultramar), met Mondlane at the United Nations when both were working there and, recognising his qualities, tried to bring him to the Portuguese side by offering to him a post in Portuguese Mozambique's administration. However, Mondlane showed little interest in the offer and later joined the Mozambican pro-independence movements in Tanzania, who lacked a credible leader.[8] In 1962 Mondlane was elected president of the newly formed Mozambican Liberation Front (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique or FRELIMO), which was composed of elements from smaller independentist groups. In 1963 he settled FRELIMO headquarters outside of Mozambique in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Supported both by several Western countries and the USSR, as well as by many African states, FRELIMO began a guerrilla war in 1964 to obtain Mozambique's independence from Portugal. In FRELIMO's early years, its leadership was divided: the faction led by Mondlane wanted not merely to fight for independence but also for a change to a socialist society; dos Santos, Machel and Chissano and a majority of the Party's Central Committee shared this view. Their opponents, prominent among whom were Nkavandame and Simango, wanted independence, but not a fundamental change in social relations. The socialist position was approved by the Second Party Congress, held in July 1968; Mondlane was re-elected party president, and a strategy of protracted war based on support among the peasantry (as opposed to a quick coup attempt) was adopted.

Death

[edit]In 1969, a book containing a bomb was sent to Mondlane at the FRELIMO Headquarters in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It exploded when he opened the package in the house of an American friend, Betty King, killing him.[9] Various parties have been implicated as potentially responsible for his assassination, including rivals within FRELIMO, Tanzanian politicians, the Portuguese secret service, and Aginter Press.[10] Former International and State Defense Police (PIDE) Agent Oscar Cardoso claims that PIDE Agent Casimiro Monteiro planted the bomb that killed Eduardo Mondlane.[citation needed]

Legacy and homages

[edit]Mondlane's death was mourned at a funeral in 1969 which was officiated by his Oberlin classmate and friend the Reverend Edward Hawley, who said during the ceremonies that Mondlane "...laid down his life for the truth that man was made for dignity and self-determination."

By the early 1970s, FRELIMO's 7,000-strong guerrilla force had wrested control of some countryside areas of the central and northern parts of Mozambique from the Portuguese authorities. The independentist guerrilla was engaging a Portuguese force of approximately 60,000 military, which was almost all concentrated in the area of Cahora Bassa where the Portuguese administration was finalising the construction of a major hydroelectric dam, one of many facilities and improvements that the Portuguese provincial administration's development commission was rapidly developing since the 1960s. The 1974 overthrow of the Portuguese ruling regime after a leftist military coup in Lisbon brought a dramatic change of direction in Portugal's policy regarding its overseas provinces, and on 25 June 1975, Portugal handed over power to FRELIMO and Mozambique became an independent nation.

Mondlane's wife Janet Rae Johnson served in various government positions, and his daughter Nyeleti Mondlane became Minister of Youth and Sports and later of Gender, Children and Social Action.

Eduardo Mondlane University

[edit]In 1975, the Universidade de Lourenço Marques founded by the Portuguese and given the name of the capital of Portugal's Overseas Province of Mozambique, Lourenço Marques (now Maputo, Mozambique), was renamed Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, or Eduardo Mondlane University. It is located in the capital city of independent Mozambique.[11]

Eduardo Mondlane Lecture Series

[edit]Syracuse University's Africa Initiative hosts the Eduardo Mondlane Brown Bag Lecture Series that invites speakers worldwide to participate in Africana studies.

Works

[edit]- Eduardo Mondlane, The Struggle for Mozambique. 1969, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Helen Kitchen, "Conversations with Eduardo Mondlane", in Africa Report, No. 12 (November 1967), p. 51.

- George Roberts. “The Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane: FRELIMO, Tanzania, and the Politics of Exile in Dar es Salaam.” Cold War History 17:1 (February 2017): 1-19. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14682745.2016.1246542.

- Robert, Faris, Liberating Mission in Mozambique. Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane, Eugene OR: Pickwick, 2014.

References

[edit]- ^ "In memory of Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane '53". Alumni News & Notes. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Eduardo Mondlane | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Eduardo Mondlane: The man behind Mozambique's unity". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Cossa, Jose. 2012. "Reviving the Memory of Eduardo Mondlane in Syracuse: Links between Syracuse and a Mozambican Liberation Leader," Peace Newsletter #819 (November–December), pp. 11–12. Syracuse Peace Council.

- ^ Faris, Robert, Liberating Mission in Mozambique. Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane., Eugene OR: Pickwick, 2014.

- ^ "Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane '53". Oberlin.edu. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Silvério Ronguane,90 Anos depois do seu nascimento. 41 anos depois da sua morte! Toda verdade sobre Mondlane,Dondza Editora, 2010.

- ^ Kenneth Maxwell, The Making of Portuguese Democracy, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-58596-1, ISBN 978-0-521-58596-5

- ^ João Vaz de Almada, "Moçambique tem de descobrir Eduardo Mondlane", Verdade, 31 January 2009.

- ^ "H-Diplo Article Review 707 on "The Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane: FRELIMO, Tanzania, and the Politics of Exile in Dar es Salaam." | H-Diplo | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- 1920 births

- 1969 deaths

- Mozambican communists

- People from Gaza Province

- Oberlin College alumni

- Mozambican independence activists

- Assassinated Mozambican politicians

- Deaths by letter bomb

- People murdered in Tanzania

- Northwestern University alumni

- FRELIMO politicians

- Syracuse University faculty

- Mozambican anthropologists

- Mozambican expatriates in the United States

- Harvard University alumni

- 1960s murders in Tanzania

- 1969 crimes in Tanzania

- 1969 murders in Africa

- 20th-century anthropologists

- Mozambican expatriates in Tanzania

- Mozambican expatriates in South Africa

- Mozambican expatriates in Portugal

- Tsonga people

- Politicians assassinated in the 1960s

- Deaths by explosive device