Gujranwala

Gujranwala

گوجرانوالہ | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: City of Wrestlers[1] | |

Location in Pakistan | |

| Coordinates: 32°9′24″N 74°11′24″E / 32.15667°N 74.19000°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Gujranwala |

| District | Gujranwala |

| Tehsil | Gujranwala City, Gujranwala Saddar |

| Autonomous towns | 7 |

| Union councils | 19 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan Corporation[2] |

| • Deputy Commissioner (Administrator in absence of Mayor) | Saira Umer[3] |

| • Deputy Mayor(s) | None (Vacant)[3] |

| Area | |

| • City | 240 km2 (90 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,198 km2 (1,235 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 231 m (758 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 2,511,118 |

| • Rank | 5th, Pakistan |

| • Density | 10,000/km2 (27,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PKT) |

| Postal code | 52250 |

| Area code | 055 |

| Website | gujranwaladivision |

Gujranwala (Punjabi / Urdu: گوجرانوالہ; pronounced [ɡʊd͡ʒᵊɾãːʋaːlaː]) is a city and capital of Gujranwala Division located in Pakistan. It is also known as "City of Wrestlers" and is quite famous for its food.[6] It is the 5th most populous city proper after Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad and Rawalpindi respectively. Founded in the 18th century, Gujranwala is a relatively modern town compared to the many nearby millennia-old cities of northern Punjab. The city served as the capital of the Sukerchakia Misl state between 1763 and 1799, and is the birthplace of the founder of the Sikh Empire, Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Gujranwala is now Pakistan's third largest industrial centre after Karachi and Faisalabad,[7] and contributes 5% to 9% of Pakistan's national GDP.[8] The city is part of a network of large urban centres in north-east Punjab province that forms one of Pakistan's mostly highly industrialized regions.[9] Along with the nearby cities of Sialkot and Gujrat, Gujranwala forms part of the so-called "Golden Triangle" of industrial cities with export-oriented economies.[10][7]

Etymology

Gujranwala's name means "Abode of the Gujjars" in Punjabi, and was named after the Gujjar tribe that live in northern Punjab.[11][12] One local narrative suggests that the town was named after a Gujjar, Choudhry Gujjar, owner of the town's Persian wheel that supplied water to the town.[7] Evidence suggests, however, that the city derives its name from Serai Gujran (meaning "inn of Gujjars"), a village once located near what is now Gujranwala's Khiyali Gate.[7]

History

Founding

Gujranwala was founded by Gurjars in the eighteenth century[13] however the exact origins of Gujranwala are unclear. Unlike the ancient nearby cities of Sialkot and Lahore, Gujranwala is a relatively modern city. It may have been established as a village in the middle of the 16th century.[14] Locals traditionally believe that Gujranwala's original name was Khanpur Sansi, though recent scholarship suggests that the village was possibly Serai Gujran instead – a village once located near what is now Gujranwala's Khiyali Gate that was mentioned by several sources during the 18th-century invasion of Ahmad Shah Abdali.[7]

Sikh

In 1707, with the death of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, Mughal power began to rapidly weaken especially following Nader Shah's invasion in 1739 and then completely dissipated from the Punjab region due to the invasions of Ahmad Shah Abdali who raided Punjab many times between 1747 and 1772 causing much devastation and chaos.[15]

Abdali's control over the region began to weaken in the latter part of the 18th century with the rise of the Sikh Misls (independent chieftainships usually consisting of the chief's kinsmen) who overran Punjab.[15] Charat Singh, ruler of the Sukerchakia Misl, established himself in a fort which he had built in the area of Gujranwala between 1756 and 1758.[7]

Nuruddin, a Jammu-based Afghan (Pashtun) general, was ordered by Abdali to subdue the Sikhs but was driven back at Sialkot by Sikh soldiers led by Charat Singh.[15] In 1761, Khwaja Abed Khan, Abdali's governor in Lahore, tried to besiege Charat Singh's base in Gujranwala but the bid misfired. The Sikh misls rallied to his support by attacking Afghan officers wherever they were found.[15] A fleeing Abed Khan was pursued by Sikh contingents led by the Ahluwalia misl into Lahore, where he was killed.[15] Charat Singh made Gujranwala the capital of his misl in 1763.[7][16]

In a 1774 battle waged in Jammu, Charat Singh of the Sukerchakia misl and Jhanda Singh of the powerful Bhangi misl, fighting on opposite sides, were both killed.[15] Before his death, Charat Singh had become master of large and contiguous territories in the three doabs between the Indus and the Ravi. He was succeeded by his son Maha Singh who added to the lands that Charat Singh had not only captured but also capably administered.[15]

In the Gujranwala area in the 1770s, the Jat Chathas of Wazirabad and Rajput Bhattis of Hafizabad (Muslims in both cases) offered 'fierce resistance' to the Sukerchakias, whose attack was aided by Sahib Singh of the Bhangi misl.[15] Describing the conflict, the (British) writer of the Gujranwala Gazetteer wrote that besieged for weeks in his fortress, Ghulam Muhammad Chatha eventually surrendered after Maha Singh assured him safe passage to Mecca, but the promise was 'basely broken' when Ghulam Muhammad was shot and his fortress razed to the ground.[15] Rasoolnagar (Prophet's city) which belonged to the Chathas was renamed Ramnagar (Ram's city) to humiliate the Muslims.[15] The Gazetteer noted that the treacherous killing of Chatha and his resistance was remembered 'in many a local ballad' in Gujranwala.[15] The Bhattis of Hafizabad tehsil, who were Muslim Rajputs, did not cease their resistance to the Sukerchakias until 1801 when their leaders were killed and their possessions captured.[15] Some Bhattis fled to Jhang.[15]

Ranjit Singh, Maha Singh's son and successor who would later go on to establish the Sikh Empire, was born in 1780 in Gujranwala's Purani Mandi market.[16] Ranjit Singh maintained Gujranwala as his capital initially after rising to power in 1792. His most famous military commander Hari Singh Nalwa, who was also from Gujranwala, built a high mud wall around Gujranwala during this era and established the city's new grid street-plan that exists until the present day.[7] Gujranwala remained Ranjit Singh's capital until he captured Lahore from the Durrani Afghans in 1799, at which point the capital was moved there, leading to the relative decline of Gujranwala in favour of Lahore.[17]Jind Kaur, the last queen of Ranjit Singh and mother of Duleep Singh, was born in Gujranwala in 1817.[18]

By 1839, the city's bazaars were home to an estimated 500 shops, while the city had been surrounded by a number of pleasure gardens, including one established by Hari Nalwa Singh that was famous for its vast array of exotic plants.[7]

British

The area was captured by the British Empire in 1848, and rapidly developed thereafter.[7] Gujranwala was incorporated as a municipality in 1867,[19] and the city's Brandreth, Khiyali, and Lahori Gates built atop the site of Sikh-era gates were completed in 1869.[7] A new clocktower was built in central Gujranwala to mark the city's centre in 1906.

Christian missionaries were brought to the region during British colonial rule, and Gujranwala became home to numerous churches and schools.[7] The city's first Presbyterian Church was established in 1875 in the Civil Lines area – a settlement built one mile north of the old city to house Gujranwala's European population. A theological seminary was established in 1877, and a Christian technical school in 1900.[7]

The North-Western Railway connected Gujranwala with other cities in British India by rail in 1881.[11] The major Sikh higher learning institution, Gujranwala Guru Nanak Khalsa College, was founded in Gujranwala in 1889, though it later shifted to Ludhiana.[7] The nearby Khanki Headworks were completed in 1892 under British rule, and helped irrigate 3 million acres in the province. Gujranwala's population, according to the 1901 census of British India, was 29,224.[11] The city continued to grow rapidly for the remainder of British rule.

Riots erupted in Gujranwala following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in April 1919. These were some of most violent riots in response to the massacre in all of British India.[7] Riots lead to the damage of the city's railway station and burning of the city's Tehsil Office, Clock Tower, Dak Bangla and city courts.[7] Much of the city's historical record was burnt in the attacked offices.[7] Protestors in the city, nearby villages, and a procession from Dhullay were fired upon with machine-guns mounted to low-flying planes, and subjected to aerial bombardment from the Royal Air Force under the control of Reginald Edward Harry Dyer.[7][20][21]

According to the 1941 census, 269,528 out of the Gujranwala District's 912,234 residents were non-Muslim.[22] 54.30% of Gujranwala city residents were Muslims prior to Partition, though non-Muslims controlled much of the city's economy.[7] Hindus and Sikhs together owned two-thirds of Gujranwala's properties.[7] Sikhs were concentrated in the localities of Guru Nanak Pura, Guru Gobind Garh, and Dhullay Mohallah, while Hindus were dominant in Hakim Rai, Sheikhupura Gate area and Hari Singh Nalwa Bazaar. Muslims were concentrated in Rasul Pura, Islam Pura and Rehman Pura.[7]

Partition

Following the Independence of Pakistan and the aftermath of the Partition of British India in 1947, Gujranwala was the site of some of the worst rioting in Punjab.[7][23] Large swathes of Hindu and Sikh localities were attacked or destroyed.[7][23] Rioters in the city gained notoriety for attacks, with the city's Muslim Lohar (blacksmiths) particularly carrying out brutal attacks.[23] In retaliation for attacks against a trainload of refugees by Sikh rioters at Amritsar railway station on 22 September that resulted in the deaths of 3,000 Muslims over the course of three hours,[23][24] rioters from Gujranwala attacked a trainload of Hindus and Sikhs fleeing towards India on 23 September,[23] killing 340 refugees in the nearby town of Kamoke.[24] Partition riots in Gujranwala resulted in systematic violence against the city's minorities,[23] and may constitute an act of ethnic cleansing by modern standards.[23] Gujranwala became home to Muslim refugees who were fleeing from the widespread anti-Muslim pogroms that depopulated eastern Punjab in India of almost its entire Muslim population.[23] Refugees in Gujranwala were mainly those who had fled from the cities of Amritsar, Patiala, and Ludhiana in what had become the Indian state of East Punjab.[7]

Modern

The influx of Muslim refugees into Gujranwala drastically altered the city's form. By March 1948, over 300,000 refugees had been resettled in Gujranwala District.[25] Many refugees found post-Partition Gujranwala lacking in opportunities, causing some to move south to Karachi.[25] The refugee population mostly settled in localities that were mostly non-Muslim, like Gobindgarh, Baghbanpura and Nanakpura.[25]

Suburban districts were rapidly laid, including Satellite Town in 1950, which was designed mostly to house wealthy and upper-middle-class refugees.[25] D-Colony was built in 1956 for poorer Kashmiri refugees,[25] and Model Town in the 1960s.[7] The city experienced strong industrial growth during this period. In 1947, there were only 39 registered factories – a number which rose to 225 by 1961.[25] The city's colonial-era metal-working industry continued to grow, while the city became a centre of hosiery manufacturing that was run by refugees from Ludhiana.[25] The city's jewellery-trade had been run by Hindus but came under the control of refugees from Patiala.[25]

Gujranwala's economy continued to grow into the 1970s and 1980s.[7] New development continues, such as the opening of a 5,774-foot long flyover that functions as an elevated urban expressway,[7] as well as the nearby Sialkot International Airport which serves the entire Golden Triangle region, and is Pakistan's first privately owned commercial airport.[26] Institutions of higher learning have also been established in the city since independence. The Sialkot-Lahore Motorway, opened in 2020, passes near Gujranwala.

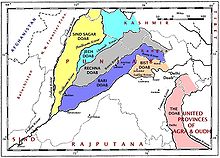

Geography

Gujranwala sits at the heart of the Rechna Doab, a strip of land between the Chenab in the north, and Ravi River in the south. Gujranwala is also part of the Majha, a historical region of northern Punjab. The city was built upon the plains of Punjab, and the surrounding region is an unbroken plain devoid of topographical diversity.[27]

Gujranwala is 226 metres (744 ft) above sea level, sharing borders with Ghakhar Mandi and several towns and villages. About 80 kilometres (50 mi) south is the provincial capital, Lahore. Sialkot and Gujrat lie to its north. Gujrat connects Gujranwala with Bhimber, Azad Kashmir, and Sialkot connects it with Jammu. About 160 kilometres (99 mi) southwest is Faisalabad. To its west are Hafizabad and Pindi Bhattian, which connect Gujranwala to Jhang, Chiniot and Sargodha.

Climate

Gujranwala has a hot semi-arid climate (BSh),[28] according to the Köppen-Geiger system, and changes throughout the year. During summer (June to September), the temperature reaches 36–42 °C (97–108 °F). The coolest months are usually November to February when the temperature can drop to an average of 7 °C (45 °F). The highest precipitation months are usually July and August when the monsoon reaches Punjab. During the other months, the average rainfall is about 25 millimetres (0.98 in). October to May have little rainfall.[29]

| Climate data for Gujranwala | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

33.7 (92.7) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.8 (105.4) |

36.1 (97.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.8 (92.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31 (1.2) |

30 (1.2) |

29 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

19 (0.7) |

46 (1.8) |

147 (5.8) |

168 (6.6) |

65 (2.6) |

9 (0.4) |

5 (0.2) |

14 (0.6) |

581 (22.9) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org, altitude: 225m[28] | |||||||||||||

Urban form

Gujranwala's oldest precincts were laid according to the new city plan devised by Hari Singh Nalwa, following Ranjit Singh's establishment of Gujranwala as his capital in 1792. A street plan based mostly on a grid plan was implemented, with bazaars intersecting one another at 90-degree angles. Some of the blocks are rectangular in shape, resulting in a polygonal shaped old city. This old city was then enclosed by a high mud wall with gates and a fort that was built immediately north of the old city. The city's Sheranwala Bagh was also expanded under Hari Singh Nalwa's direction.[7]

Gujranwala's old city is centred on the Shahi (Royal) Bazaar. The old city is home to many of the city's pre-Partition houses of worship for Hindus and Sikhs. The Hindu Devi Talab temple was once famous for its large water-tank, and remains in good condition despite being used as a residence for a family who fled Patiala.[30] The Sikh Gurdwara Damdama Sahib is located near the Devi Talab Temple, is important in Sikhism for its association with Baba Sahib Singh Bedi, a Sikh saint.[30] An old gurdwara is also located near the Chashma Chowk intersection near Shahi Bazaar.[30]

Gujranwala was also home to a Jain community, called Bhabra in Punjab. In the heart of the town, Lala Mubdas Jain Mandir is present. The samadhi of Jain Acharya Atmaramji (also known as Acharya Vijayanandsuri, who died on 20 May 1896.[31] The samadhi, now being restored, was visited by Jain Acharya Dharmadhurandar Suri in on 28 May 2023, along with other Jain munis and lay Jains after a gap to more than 75 years.[32]

Gujranwala grew rapidly following British rule, and connection of the city to the railways of British India. The city grew outside of the city's walls, requiring new bazaars to be laid, which were done in a radial plan centred on the old city.[7] Some historic structures like the Haveli of Sardar Mahan Singh were torn down by the British and replaced with other structures. The city's Brandreth, Lahori, and Khiyali Gates were built atop the city's demolished original gates, while Mahan Singh's haveli was transformed into a public square named Ranjit Ganj.[7] The city's boundaries remained mostly west of the railways' line prior to 1947.[7]

The Civil Lines neighbourhood was built for European residents approximately one mile north of the old city. The area was characterized by bungalows, large and verdant lawns, and shady tree-lined avenues.[7] Civil Lines is where the city's Presbyterian Church was built in 1875, while the city's Theological Seminary was established here in 1877. The Christian Technical Training Center followed suit in 1900.[7] The city's elite Hindus and Sikhs eventually also settled in small numbers in Civil Lines.[7] Several of their mansions still remain in the area including those of Charan Singh, Banarsi Shah, as well as other buildings such as Islamia College and Khurshid Manzil.[7]

Growth occurred mostly in areas northwest and southeast of the city immediately after independence until 1965 along routes emanating from old Gujranwala. Satellite Town was established on the southwest side in 1950. Areas northeast and southwest of the city were the sites of most growth between 1965 and 1985. The growth grows outwards mostly evenly after 1985 until the present time.[7] Much of the growth has been unplanned due to poor enforcement of development guidelines and lax enforcement of property laws.[7]

Demography

Gujranwala is the 5th largest city in Pakistan by population. Since the 2000s the population growth rate of Gujranwala has averaged at 3.0%. The population growth rate is projected to slow down to 2.51% by 2035.[33]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 22,884 | — |

| 1891 | 26,785 | +17.0% |

| 1901 | 29,224 | +9.1% |

| 1911 | 29,472 | +0.8% |

| 1921 | 37,887 | +28.6% |

| 1941 | 85,000 | +124.4% |

| 1951 | 121,000 | +42.4% |

| 1961 | 196,000 | +62.0% |

| 1972 | 324,000 | +65.3% |

| 1981 | 601,000 | +85.5% |

| 1998 | 1,133,000 | +88.5% |

| 2000 | 1,208,940 | +6.7% |

| 2010 | 1,647,271 | +36.3% |

| 2020 | 2,229,220 | +35.3% |

| Source: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/gujranwala-population | ||

| Religious group |

1881[35][36][37] | 1891[38]: 68 [39] | 1901[40]: 44 [41]: 26 | 1911[42]: 23 [43]: 19 | 1921[44]: 25 [45]: 21 | 1931[46]: 26 | 1941[34]: 32 | 2017[47] | 2023[48] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

11,820 | 51.65% | 14,049 | 52.45% | 15,525 | 53.12% | 16,398 | 55.64% | 20,622 | 54.43% | 33,241 | 56.61% | 45,904 | 54.3% | 2,272,402 | 96.65% | 2,762,265 | 96.78% |

| Hinduism |

9,114 | 39.83% | 9,909 | 36.99% | 10,390 | 35.55% | 8,547 | 29% | 11,669 | 30.8% | 16,958 | 28.88% | 24,378 | 28.83% | 104 | 0% | 482 | 0.02% |

| Sikhism |

1,396 | 6.1% | 2,020 | 7.54% | 2,181 | 7.46% | 3,200 | 10.86% | 3,571 | 9.43% | 5,879 | 10.01% | 11,016 | 13.03% | — | — | 87 | 0% |

| Jainism |

413 | 1.8% | 522 | 1.95% | 700 | 2.4% | 713 | 2.42% | 683 | 1.8% | 978 | 1.67% | 1,343 | 1.59% | — | — | — | — |

| Christianity |

— | — | 284 | 1.06% | 428 | 1.46% | 614 | 2.08% | 1,342 | 3.54% | 1,660 | 2.83% | 1,893 | 2.24% | 76,598 | 3.26% | 89,897 | 3.15% |

| Zoroastrianism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | — | — | — | — | 3 | 0% |

| Judaism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Buddhism |

— | — | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ahmadiyya |

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1,901 | 0.08% | 1,275 | 0.04% |

| Others | 141 | 0.62% | 1 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 0.01% | 209 | 0.01% | 122 | 0% |

| Total population | 22,884 | 100% | 26,785 | 100% | 29,224 | 100% | 29,472 | 100% | 37,887 | 100% | 58,716 | 100% | 84,545 | 100% | 2,351,214 | 100% | 2,854,131 | 100% |

Economy

Gujranwala is the Pakistan's third largest centre of industrial production, after Karachi and Faisalabad. Gujranwala, along with the nearby industrial cities of Sialkot and Gujrat City, form what is sometimes referred to as the Golden Triangle in reference to their relative prosperity and export-oriented industrial base.[7] The city's industries employ up to 500,000 people,[49] while the city's GDP makes up 5% of Pakistan's overall economy.[8]

An estimated 6,500 small and medium enterprises,[50] 25,000 cottage units, and some large factories, are located in and around the city as of 2002[25] -and are engaged in the manufacture of a wide variety of goods.[51][52] The city is the centre for manufacture and export of sanitary fittings and wares in Pakistan, with over 200 producers based in Gujranwala.[50][16] More than 60 producers of auto parts are found in the city.[50] The city is well known as a centre for manufacturing electric fans – with 150 small and medium enterprises in Gujranwala tied to the electric fan industry.[53] The city is Pakistan's third largest centre for iron and steel manufacturing – reflecting Gujranwala's historic association with metalworking since the migration of the Lohar clan of blacksmiths to the city during the colonial era.[25] The city has been a centre of hosiery-manfuacture since the migration of refugees primarily from Ludhiana in 1947.[25]

Textiles, apparel, yarn, and other textile goods are also produced in Gujranwala.[16] Other manufacturing based in the city include rice, plastic, cutlery, coolers and heaters, agricultural tools and equipment, carpets, glass goods, surgical equipment, leather products, and machinery for military uses, domestic appliances, motorcycles, and food products.[7] The rural regions surrounding Gujranwala are heavily engaged in the production of wheat and are yield more wheat per acre than the national average.[54] Gujranwala District is also the most productive region for rice-growing in Punjab.[54]

In 2010, Gujranwala was rated number 6 out of Pakistan's top 13 cities in order of ease of doing business by the World Bank, and was ranked the second-best in Pakistan for construction permits.[55] Pakistan's electric shortages of the 2010s severely stymied the city's growth. Industrial units in the city suffered an average of 2872 hours per year in Gujranwala in 2012.[56] By the end of 2017, the supply of electricity had drastically improved with augmented electric generation as a result of new power-stations coming online.[57] Improved supplies of electricity contributed to the country's double-digit rise in exports in the second half of 2017.[58]

Transportation

Road

Gujranwala is situated along the historic Grand Trunk Road that connects Peshawar to Islamabad and Lahore. The Grand Trunk Road also provides access to the Afghan border via the Khyber Pass, with onward connections to Kabul and Central Asia via the Salang Pass. The Karakoram Highway provides access between Islamabad and western China, and an alternate route to Central Asia via Kashgar, China.

Gujranwala is connected to Lahore by Sialkot-Lahore Motorway. The motorway passes east of the Grand Trunk Road, and terminates near the Sialkot International Airport. Plans for the motorway's extension farther north to Kharian near Gujrat City were announced in late 2017.[59]

Rail

Gujranwala railway station serves as a stop along Pakistan's 1,687 kilometres (1,048 mi)-long Main Line-1 railway that connects the city to the port city of Karachi to Peshawar.

The entire Main Line-1 railway track between Karachi and Peshawar is to be overhauled at a cost of $3.65 billion for the first phase of the project,[60] with completion by 2021.[61] Upgrading of the railway line will permit train travel at speeds of 160 kilometres per hour, versus the average 60 to 105 km per hour speed currently possible on existing track.[62]

Air

Gujranwala has no airport of its own. The city is instead served by airports in nearby cities, including the Allama Iqbal International Airport in Lahore that offers non-stop flights to Europe, Canada, Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Gujranwala is also serviced by the nearby Sialkot International Airport – Pakistan's first privately owned commercial airport. Built-in 2007, the airport offers non-stop service to the Middle East, as well as domestic locations.

Public transportation

Gujranwala has a small scale centrally managed public transportation system known as a city tour. It has its routes from Wazirabad to Kamoke mainly extended on GT road only. Uber became available in Gujranwala in early 2017[63] and was soon followed by Careem.[64]

Administration

Gujranwala and its environs were amalgamated into a district in 1951. The Gujranwala Development Authority was established in 1989 to oversee economic and infrastructure development in the city. The city is currently administered by the City District Government Gujranwala (CDGG) and Gujranwala Metropolitan Corporation, while development is generally under the office of the Gujranwala Development Authority. In 2007, the city was re-classified as a city district with 7 constituent municipalities: Aroop, Kamonke, Khiali Shahpur, Nandipur, Nowshera Virkan, Qila Didar Singh, and Wazirabad Towns.[7]

In December 2019, Gujranwala Municipal Corporation was upgraded into Metropolitan Corporation under Punjab Local Government Act 2019.[2]

Education

Gujranwala city's adult literacy rate in 2008 was 73%,[65] which rose to 87% in the 15–24 age group throughout Gujranwala District,[66] including rural areas. The city is also home to the Gujranwala Theological Seminary which was established in Sialkot in 1877, and moved to Gujranwala in 1912.[67] The Army Aviation School of the Pakistan Air Force was moved to Gujranwala in 1987 from Dhamial.[68] Many institutes are established for higher education such as:

- University of Sargodha, Gujranwala Campus

- University of Central Punjab, Gujranwala Campus

- GIFT University, Gujranwala

- University of the Punjab, Gujranwala Campus

Sports

Gujranwala has the multipurpose Jinnah Stadium, which has capacity of 20,000 spectators. It has hosted matches of the 1987 and 1996 Cricket World Cup.

See also

References

- ^ "Gujranwala- The City of Wrestlers". 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b Khan, Iftikhar A. (27 December 2019). "Every fourth district in Punjab to have a metropolitan corporation". Dawn. Pakistan.

- ^ a b "Administrators' appointments planned as Punjab LG system dissolves today". The Nation (newspaper). 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Complaint Management System: Municipal Corporation, Gujranwala". The Urban Unit, Planning & Development (Punjab). Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL: PUNJAB" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Gujranwala- The City of Wrestlers". Daily The Patriot. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an Naz, Neelum. "Historical Perspective of Urban Development of Gujranwala". Dept. of Architecture, UET, Lahore. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Punjab at a Glance". Punjab Board of Investment and Trade. Government of Punjab. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Azhar, Annus; Adil, Shahid. "Effect of Agglomeration on Socio-Economic Outcomes: A District Level Panel study of Punjab" (PDF). Pakistan Institute of Developmental Economics. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Mehmood, Mirza, Faisal; Ali, Jaffri, Atif; Saim, Hashmi, Muhammad (21 April 2014). An assessment of industrial employment skill gaps among university graduates: In the Gujrat-Sialkot-Gujranwala industrial cluster, Pakistan. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 12, page 363 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". dsal.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar; Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti (1954). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age. G. Allen & Unwin. p. 64.

- ^ Mahmood, Amjad (22 March 2021). "The importance of Gujranwala". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Gazetteer of the Gujranwala District, 1883-4. Punjab Govt. 1895. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Minhas, Salman (2004). "Gujranwala – its people and tradition of light industry". The South Asian. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Gujranwala". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Bansal, Bobby (2015). Remnants of the Sikh Empire: Historical Sikh Monuments in India & Pakistan. Hay House, Inc. ISBN 978-9384544935.

- ^ Reports on the Administration of the Punjab. 1872. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Qutubuddin Aziz (2001). Jinnah and Pakistan. Islamic Media Corporation. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Sarkar, Rasul Pura, Islam Pura and Rehamn PuraSumit (1989). Modern India 1885–1947. Springer. ISBN 1349197122. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abid, D. (1989). A Fresh Look at the Redcliffe Award. Grassroots.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chattha, Ilyas (2011). Partition and Locality: Violence, Migration, and Development in Gujranwala and Sialkot, 1947-1961. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b "3,000 Dead in Indian Train Massacre". Australian Associated Press. 26 September 1947. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Chattha, Ilyas Ahmad (September 2009). "Partition and Its Aftermath: Violence, Migration and the Role of Refugees in the Socio-Economic Development of Gujranwala and Sialkot Cities, 1947-1961" (PDF). University of Southampton. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Pakistan's business climate If you want it done right". The Economist. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Ball, W.E. (1874). Report on the Revision of the Land Revenue Settlement of the Gujranwala District. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Climate: Gujranwala – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Jinnah Stadium, Gujranwala – Monthly Averages

- ^ a b c Jatt, Zahida Rehman (December 2015). "Exploring Tourism Opportunities: Documentation of the Use of Spaces of the Pre- Partitioned Temples and Gurudwaras in Punjab, Pakistan". Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design. 5 (2). ISSN 2231-4822. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ The legend of Atmaram Ji’s Samadhi, Tania Qureshi, Daily Times, MAY 28, 2019

- ^ पूजनीय आत्म वल्लभजी के गुरुदेव आत्मारामजी समाधि धाम में जैनाचार्य पूजनीय धर्मधुरंधर जी मा.सा का आगमन, PALI SIROHI ONLINE, Nagendra Agrawal, May 28, 2023

- ^ "Gujranwala Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com.

- ^ a b "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1941 VOLUME VI PUNJAB". Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. I." 1881. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057656. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. II". 1881. p. 520. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057657. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1881 Report on the Census of the Panjáb Taken on the 17th of February 1881, vol. III". 1881. p. 250. JSTOR saoa.crl.25057658. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Baines, Jervoise Athelstane; India Census Commissioner (1891). "Census of India, 1891. General tables for British provinces and feudatory states". JSTOR saoa.crl.25318666. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Edward Maclagan, Sir (1891). "The Punjab and its feudatories, part II--Imperial Tables and Supplementary Returns for the British Territory". JSTOR saoa.crl.25318669. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. Vol. 1A, India. Pt. 2, Tables". 1901. JSTOR saoa.crl.25352838. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. [Vol. 17A]. Imperial tables, I-VIII, X-XV, XVII and XVIII for the Punjab, with the native states under the political control of the Punjab Government, and for the North-west Frontier Province". 1901. JSTOR saoa.crl.25363739. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Edward Albert Gait, Sir; India Census Commissioner (1911). "Census of India, 1911. Vol. 1., Pt. 2, Tables". Calcutta, Supt. Govt. Print., India, 1913. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393779. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 14, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393788. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 1, India. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. JSTOR saoa.crl.25394121. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 15, Punjab and Delhi. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430165. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "CENSUS OF INDIA, 1931 VOLUME XVII PUNJAB PART II TABLES". Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Final Results (Census-2017)". Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results Table-9 Population by sex, religion and rural/urban". Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "Gujranwala's role in national economy". Dawn. Pakistan. 17 August 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "Gujranwala Business Centre". Govt of Punjab. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Jamal, Nasir (10 November 2014). "Industry profile of Gujranwala". Dawn. Pakistan.

- ^ "Gujranwala Business Centre". Gujranwala Business Centre.

- ^ "Fans". TRTA Pakistan. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Agricultural Survey of Gujranwala" (PDF). State Bank of Pakistan. 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Gujranwala – Pakistan". World Bank. 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Planning & Development Department (March 2015), PUNJAB GROWTH STRATEGY 2018 Accelerating Economic Growth and Improving Social Outcomes, Govt of Punjab

- ^ "Govt announces zero loadshedding in parts of country". Dawn. Pakistan. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Non-textile exports grew 13.6pc in July–October". Dawn. Pakistan. 26 November 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "49km Sambrial-Kharian motorway on the cards". The Nation. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "PURCHASE OF POWER: PAYMENTS TO CHINESE COMPANIES TO BE FACILITATED THROUGH REVOLVING FUND". Business Recorder. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Pakistan to get Chinese funds for upgrading rail links, building pipeline". Hindustan Times. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

The project is planned to be completed in two phases in five years by 2021. The first phase will be completed by December 2017 and the second by 2021.

- ^ "Karachi-Peshawar railway line being upgraded under CPEC". Daily Times. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Gujranwala joins the growing list of smart cities to offer Uber". Daily Pakistan. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Careem Launches in Multan, Gujranwala and Sialkot". PAKISTAN KA KHUDA HAFIZ. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Punjab 2007-08" (PDF). GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF STATISTICS. March 2009. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) Punjab 2007-08" (PDF). GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF STATISTICS. March 2009. pp. v. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "About Us". Gujranwala Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Army Aviation School". Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ 1881-1941: Data for the entirety of the town of Template, which included Gujranwala Municipality, Gujranwala Cantonment, and Gujranwala Civil Lines.[34]: 32

2017-2023: Combined urban populations of Gujranwala City Tehsil and Gujranwala Saddar Tehsil. - ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

External links

- Gujranwala Chamber of Commerce & Industry

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 713.