Trapezius

| Trapezius | |

|---|---|

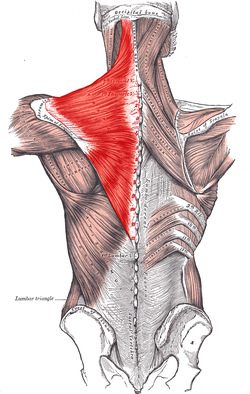

The trapezius muscle (pl.: trapezii) is a surface muscle of back, shown in red above and below. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Origin | Medial one-third of superior nuchal line, external occipital protuberance, spinous processes of vertebrae C7-T12, Nuchal ligament[1] |

| Insertion | Posterior border of the lateral one-third of the clavicle, acromion process, and spine of scapula |

| Artery | Superficial branch of transverse cervical artery or superficial cervical artery [2] |

| Nerve | Accessory nerve (motor) cervical spinal nerves C3 and C4 (motor and sensation)[3] |

| Actions | Rotation, retraction, elevation, and depression of scapula |

| Antagonist | Serratus anterior muscle, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus trapezius |

| TA98 | A04.3.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2226 |

| FMA | 9626 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The trapezius[4] is a large paired trapezoid-shaped surface muscle that extends longitudinally from the occipital bone to the lower thoracic vertebrae of the spine and laterally to the spine of the scapula. It moves the scapula and supports the arm.

The trapezius has three functional parts:

- an upper (descending) part which supports the weight of the arm;

- a middle region (transverse), which retracts the scapula; and

- a lower (ascending) part which medially rotates and depresses the scapula.

Name and history

[edit]The trapezius muscle resembles a trapezium, also known as a trapezoid, or diamond-shaped quadrilateral. The word "spinotrapezius" refers to the human trapezius, although it is not commonly used in modern texts. In other mammals, it refers to a portion of the analogous muscle.

Structure

[edit]

The superior or upper (or descending) fibers of the trapezius originate from the spinous process of C7, the external occipital protuberance, the medial third of the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone (both in the back of the head), and the ligamentum nuchae. From this origin, they proceed downward and laterally to be inserted into the posterior border of the lateral third of the clavicle.

The middle fibers, or transverse of the trapezius arise from the spinous process of the seventh cervical (both in the back of the neck), and the spinous processes of the first, second, and third thoracic vertebrae. They are inserted into the medial margin of the acromion, and into the superior lip of the posterior border of the spine of the scapula.

The inferior or lower (or ascending) fibers of the trapezius arise from the spinous processes of the remaining thoracic vertebrae (T4–T12). From this origin, they proceed upward and laterally to converge near the scapula and end in an aponeurosis, which glides over the smooth triangular surface on the medial end of the spine, to be inserted into a tubercle at the apex of this smooth triangular surface.

At its occipital origin, the trapezius is connected to the bone by a thin fibrous lamina, firmly adherent to the skin. The superficial and deep epimysia are continuous with an investing deep fascia that encircles the neck and also contains both sternocleidomastoid muscles.

At the middle, the muscle is connected to the spinous processes by a broad semi-elliptical aponeurosis, which reaches from the sixth cervical to the third thoracic vertebræ and forms, with that of the opposite muscle, a tendinous ellipse. The rest of the muscle arises by numerous short tendinous fibers.

It is possible to feel the muscles of the superior trapezius as they become active by holding a weight in one hand in front of the body and, with the other hand, touching the area between the shoulder and the neck.[citation needed]

- Images of the trapezius and the bones to which it attaches, with muscular attachments shown in red

-

Trapezius muscle

-

Left clavicle. Superior surface.

-

Left scapula. Posterior surface.

Innervation

[edit]Motor function is supplied by the accessory nerve.[5] Sensation, including pain and the sense of joint position (proprioception), travel via the ventral rami of the third (C3) and fourth (C4) cervical spinal nerves.[5] Since it is a muscle of the upper limb, the trapezius is not innervated by dorsal rami, despite being placed superficially in the back.

Function

[edit]Contraction of the trapezius muscle can have two effects: movement of the scapulae when the spinal origins are stable, and movement of the spine when the scapulae are stable.[5] Its main function is to stabilize and move the scapula.[5]

Scapular movements

[edit]The upper fibers elevate the scapulae, the middle fibers retract the scapulae, and the lower fibers depress the scapulae.[5]

In addition to scapular translation, the trapezius induces scapular rotation. The upper and lower fibers tend to rotate the scapula around the sternoclavicular articulation so that the acromion and inferior angles move up and the medial border moves down (upward rotation). The upper and lower fibers work in tandem with serratus anterior to upwardly rotate the scapulae, and work in opposition to the levator scapulae and the rhomboids, which effect downward rotation.

An example of trapezius function is an overhead press. When activating together, the upper and lower fibers also assist the middle fibers (along with other muscles such as the rhomboids) with scapular retraction/adduction.

The trapezius also assists in abduction of the shoulder above 90 degrees by rotating the glenoid upward. Injury to cranial nerve XI will cause weakness in abducting the shoulder above 90 degrees.

Spinal movements

[edit]When the scapulae are stable, a co-contraction of both sides can extend the neck.

Clinical significance

[edit]Dysfunction of the trapezius can result in winged scapula, sometimes further specified as "lateral winging"[6] and in an abnormal mobility or function of the scapula (scapular dyskinesia).[7] There are multiple causes of trapezius dysfunction.

Palsy

[edit]Trapezius palsy, due to damage of the spinal accessory nerve, is characterized by difficulty with arm adduction and abduction, and associated with a drooping shoulder, and shoulder and neck pain.[8] Intractable trapezius palsy can be surgically managed with an Eden–Lange procedure.

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

[edit]The trapezius muscle is one of the commonly affected muscles in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). The lower and middle fibers are affected initially, and the upper fibers are commonly spared until late in the disease.[9]

Underdevelopment

[edit]Although rare, underdevelopment or absence of the trapezius has been reported to correlate to neck pain and poor scapular control that are not responsive to physical therapy.[10] Absence of the trapezius has been reported in association with Poland syndrome.[11]

Society and culture

[edit]Exercises

[edit]- The upper portion of the trapezius can be developed by elevating the shoulders. Common exercises for this movement are any version of the clean, particularly the hang clean, and the shoulder shrug. The uppermost area can be trained through neck extension.

- Middle fibers are developed by pulling shoulder blades together. This adduction also uses the upper/lower fibers.

- The lower part can be developed by drawing the shoulder blades downward while keeping the arms almost straight and stiff.

It is mainly used in throwing, with the deltoid muscle and rotator cuff.

References

[edit]- ^ Rockwood, Charles A. (January 1, 2009). The Shoulder. ISBN 978-1416034278.

- ^ "Tufts". Archived from the original on April 22, 2003. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Dalley, Arthur F.; Moore, Keith L.; Agur, Anne M.R. (2010). Clinically oriented anatomy (6th [International] ed.). Philadelphia [etc.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer. p. 700. ISBN 978-1-60547-652-0.

- ^ Lajtai, Georg; Applegate, Gregory; Snyder, Stephen J.; Aitzetmüller, Gernot; Gerber, Christian (March 11, 2003). "trapezoid"&pg=PA89 Shoulder Arthroscopy and MRI Techniques: 20 Tables. ISBN 9783540431121.

- ^ a b c d e Bakkum, Barclay W.; Cramer, Gregory D. (January 1, 2014), Cramer, Gregory D.; Darby, Susan A. (eds.), "Chapter 4 - Muscles That Influence the Spine", Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans (Third Edition), Saint Louis: Mosby, pp. 98–134, ISBN 978-0-323-07954-9, retrieved January 8, 2021

- ^ Martin, RM; Fish, DE (March 2008). "Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5. PMC 2684151. PMID 19468892.

- ^ Panagiotopoulos AC, Crowther IM (2019). "Scapular Dyskinesia, the forgotten culprit of shoulder pain and how to rehabilitate". SICOT-J. 5: 29. doi:10.1051/sicotj/2019029. PMC 6701878. PMID 31430250.

- ^ Wiater JM, Bigliani LU (1999). "Spinal accessory nerve injury". Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 368 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1097/00003086-199911000-00003.

- ^ Parada, Stephen; Girden, Alex; Warner, Jon JP (January 17, 2019). "Evaluation and Management of Scapular Winging due to Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSH)". Cancer Therapy Advisor. Archived from the original on November 4, 2023.

- ^ Bergin, Michael; Elliott, James; Jull, Gwendolen (2011). "The Case of the Missing Lower Trapezius Muscle". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 41 (8): 614. doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.0416. PMID 21808102. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023.

- ^ Yiyit, N; Işıtmangil, T; Oztürker, C (November 2014). "The abnormalities of trapezius muscle might be a component of Poland's syndrome". Medical Hypotheses. 83 (5): 533–6. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2014.09.007. PMID 25257706.

External links

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 432 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 432 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)