Bear Bryant

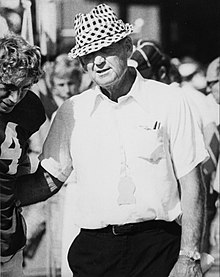

Bryant in 1973 | |

| Biographical details | |

|---|---|

| Born | September 11, 1913 Moro Bottom, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Died | January 26, 1983 (aged 69) Tuscaloosa, Alabama, U.S. |

| Playing career | |

| 1933–1935 | Alabama |

| Position(s) | End |

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |

| 1936 (spring) | Union (TN) (line) |

| 1936–1939 | Alabama (line) |

| 1940–1941 | Vanderbilt (line) |

| 1942 | Georgia Pre-Flight (ends) |

| 1944 | North Carolina Pre-Flight (line) |

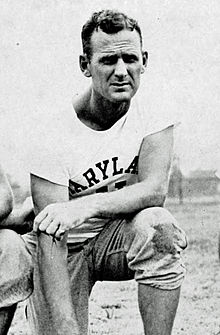

| 1945 | Maryland |

| 1946–1953 | Kentucky |

| 1954–1957 | Texas A&M |

| 1958–1982 | Alabama |

| Administrative career (AD unless noted) | |

| 1954–1957 | Texas A&M |

| 1958–1983 | Alabama |

| Head coaching record | |

| Overall | 323–85–17 |

| Bowls | 15–12–2 |

| Accomplishments and honors | |

| Championships | |

| 6 national (1961, 1964, 1965, 1973, 1978, 1979) 14 SEC (1950, 1961, 1964–1966, 1971–1975, 1977–1979, 1981) 1 SWC (1956) | |

| Awards | |

| |

| College Football Hall of Fame Inducted in 1986 (profile) | |

Paul William "Bear" Bryant (September 11, 1913 – January 26, 1983) was an American college football player and coach. He is considered by many to be one of the greatest college football coaches of all time, and best known as the head coach of the University of Alabama football team, the Alabama Crimson Tide, from 1958 to 1982. During his 25-year tenure as Alabama's head coach, he amassed six national championships and 13 conference championships. Upon his retirement in 1982, he held the record for the most wins (323) as a head coach in collegiate football history. The Paul W. Bryant Museum, Paul W. Bryant Hall, Paul W. Bryant Drive, and Bryant–Denny Stadium are all named in his honor at the University of Alabama.

He was also known for his trademark black and white houndstooth hat (even though he normally wore a plaid one), deep voice, casually leaning up against the goal post during pre-game warmups, and holding his rolled-up game plan while on the sidelines. Before arriving at Alabama, Bryant was head football coach at the University of Maryland, the University of Kentucky, and Texas A&M University.

Early life

[edit]Bryant was the 11th of 12 children who were born to Wilson Monroe Bryant and Ida Kilgore Bryant in Moro Bottom, Cleveland County, Arkansas.[1] His nickname stemmed from his having agreed to wrestle a captive bear during a carnival promotion when he was 13 years old.[2] His mother wanted him to be a minister, but Bryant told her "Coaching is a lot like preaching."[3] He attended Fordyce High School, where the 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) tall Bryant, who as an adult would eventually stand 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m), began playing on the school's football team as an eighth grader.[4][5][6] During his senior season, Bryant played offensive line and defensive end, and the team won the 1930 Arkansas state football championship.[7]

College playing career

[edit]Bryant accepted a scholarship to play for the University of Alabama in 1931.[8] Since he elected to leave high school before completing his diploma, Bryant had to enroll in a Tuscaloosa high school to finish his education during the fall semester while he practiced with the college team. Bryant played end for the Crimson Tide and was a participant on the school's 1934 national championship team.[9] Bryant was the self-described "other end" during his playing years with the team, playing opposite the big star, Don Hutson, who later became a star in the National Football League and a Pro Football Hall of Famer.[10][11] Bryant himself was second team All-Southeastern Conference in 1934, and was third team all conference in both 1933 and 1935. Bryant played with a partially broken leg in a 1935 game against Tennessee.[2] Bryant was a member of Sigma Nu fraternity, and as a senior, he married Mary Harmon, which he kept a secret since Alabama did not allow active players to be married.[2]

Bryant was selected in the fourth round by the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1936 NFL draft, but he never played professional football.[12]

Coaching career

[edit]Assistant and North Carolina Pre-Flight

[edit]After graduating from the University of Alabama in 1936, Bryant was hired as the line coach under head coach A. B. Hollingsworth at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee,[13] but he left that position when offered an assistant coaching position under Frank Thomas at the University of Alabama.[14][15] Over the next four years, the team compiled a 29–5–3 record.[16] In 1937, he was offered a position as the line coach for VMI under Pooley Hubert,[17] but Bryant ultimately declined the offered and signed a two-year contract to stay with Alabama.[18] In 1940, he left Alabama to become the line coach at Vanderbilt University under first-year Red Sanders.[19][20][21] During their 1940 season, Bryant served as head coach of the Commodores for their 7–7 tie against Kentucky as Sanders was recovering from an appendectomy.[22] After the 1941 season, Bryant was offered the head coaching job at the University of Arkansas.[23] However, Pearl Harbor was bombed soon thereafter, and Bryant declined the position to join the United States Navy. In 1942 he served as the ends coach for the Georgia Pre-Flight Skycrackers.[24][25]

Bryant then served off North Africa, on the United States Army Transport SS Uruguay, seeing no combat action.[26] On February 12, 1943, in the North Atlantic the oil tanker USS Salamonie suffered a steering fault and accidentally rammed the SS Uruguay amidships. The tanker's bow made a 70-foot (21 m) hole in Uruguay's hull and penetrated her, killing 13 soldiers and injuring 50. The Uruguay's crew contained the damage by building a temporary bulkhead and three days later she reached Bermuda. President Franklin D. Roosevelt decorated Uruguay's Captain, Albert Spaulding, with the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal for saving many lives, his ship and her cargo.[citation needed]

Bryant was later granted an honorable discharge to train recruits and coach the North Carolina Navy Pre-Flight football team.[27][28] One of the players he coached for the Navy was the future Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham.[29] While in the navy, Bryant attained the rank of lieutenant commander.[1]: 94

Maryland

[edit]

In 1945, 32-year-old Bryant met Washington Redskins owner George Marshall at a cocktail party hosted by the Chicago Tribune, and mentioned that he had turned down offers to be an assistant coach at Alabama and Georgia Tech because he was intent on becoming a head coach. Marshall put him in contact with Harry Clifton "Curley" Byrd, the president and former football coach of the University of Maryland.[30]

After meeting with Byrd the next day, Bryant received the job as head coach of the Maryland Terrapins.[31] In his only season at Maryland, Bryant led the team to a 6–2–1 record.[32] However, Bryant and Byrd came into conflict. In the most prominent incident, while Bryant was on vacation, Byrd brought back a player that was suspended by Bryant for not following the team rules. After the 1945 season, Bryant left Maryland to take over as head coach at the University of Kentucky.[33]

Kentucky

[edit]Bryant coached at Kentucky for eight seasons. Under Bryant, Kentucky made its first bowl appearance in 1947 and won its first Southeastern Conference title in 1950.[34] The 1950 Kentucky Wildcats football team finished with a school best 11–1 record and concluded the season with a victory over Bud Wilkinson's top-ranked Oklahoma Sooners in the Sugar Bowl.[35][36] The final AP poll was released before bowl games in that era, so Kentucky ended the regular season ranked #7. But several other contemporaneous polls, as well as the Sagarin Ratings System applied retrospectively, declared Bryant's 1950 Wildcats to be the national champions, but neither the NCAA nor College Football Data Warehouse recognizes this claim.[37][38] Bryant also led Kentucky to appearances in the Great Lakes Bowl, Orange Bowl, and Cotton Bowl Classic.[34] Kentucky's final AP poll rankings under Bryant included #11 in 1949, #7 in 1950, #15 in 1951, #20 in 1952, and #16 in 1953.[39] The 1950 season was Kentucky's highest rank until it finished #6 in the final 1977 AP Poll.[39]

Though he led Kentucky's football program to its greatest achievement, Bryant resigned after the 1953 season because he felt that Adolph Rupp's basketball team would always be the school's primary sport. The point shaving scandal that rocked the basketball program had Kentucky focus their energy on basketball, keeping Rupp on even after it had broken in 1952, causing the Wildcats to be given the death penalty for the 1952–53 season. Bryant tried to resign that year for Arkansas but the school did not let him. Once it was confirmed that Rupp would not resign, Bryant was even more determined to leave.[40][41] Years after leaving Lexington, when Bryant was Alabama's athletic director in 1969, he called Rupp to ask if he had any recommendations for Alabama's new basketball coach. Rupp recommended C. M. Newton, a former backup player at Kentucky in the late 1940s. Newton went on to lead the Crimson Tide to three straight SEC titles.[42]

Texas A&M

[edit]In 1954, Bryant accepted the head coaching job at Texas A&M University.[43] He also served as athletic director.[44]

The Aggies suffered through a grueling 1–9 season in 1954, which began with the infamous training camp in Junction, Texas.[45] The "survivors" were given the name "Junction Boys".[46] Two years later, Bryant led the 1956 Texas A&M Aggies football team to the Southwest Conference championship with a 34–21 victory over the Texas Longhorns at Austin.[47][48] The following year, Bryant's star back John David Crow won the Heisman Trophy, and the 1957 Aggies were in title contention until they lost to the #20 Rice Owls in Houston, amid rumors that Alabama would be going after Bryant.[49][50][51]

Again, as at Kentucky, Bryant attempted to integrate the Texas A&M squad. "We'll be the last football team in the Southwest Conference to integrate", he was told by a Texas A&M official. "Well", Bryant replied, "then that's where we're going to finish in football."[52]

At the close of the 1957 season, having compiled an overall 25–14–2 record at Texas A&M, Bryant returned to Tuscaloosa to take the head coaching position, succeeding Jennings B. Whitworth, as well as the athletic director job at Alabama.[2]

Alabama

[edit]

When asked why he returned to his alma mater, Bryant replied, "Mama called. And when Mama calls, you just have to come runnin'."[53] Bryant's first spring practice back at Alabama was much like what happened at Junction. Some of Bryant's assistants thought it was even more difficult, as dozens of players quit the team.[54] After winning a combined four games in the three years before Bryant's arrival (including Alabama's only winless season on the field in modern times), the Tide went 5–4–1 in Bryant's first season.[55][56][57][58][59] The next year, in 1959, Alabama beat Auburn and appeared in the inaugural Liberty Bowl, the first time the Crimson Tide had beaten Auburn or appeared in a bowl game in six years.[60][61][62] In the 1960 season, Bryant led Alabama to a 8–1–2 record and a #9 ranking in the final AP Poll.[63] In 1961, with quarterback Pat Trammell and football greats Lee Roy Jordan and Billy Neighbors, Alabama went 11–0 and defeated Arkansas 10–3 in the Sugar Bowl to claim the national championship.[64][65]

The next three years (1962–1964) featured Joe Namath at quarterback and were among Bryant's finest.[66] The 1962 Crimson Tide went 10–1, and the season ended with a 17–0 victory in the Orange Bowl over Bud Wilkinson's Oklahoma Sooners. The Crimson Tide finished #5 in the AP Poll[67] The 1963 Crimson Tide went 9–2, and the ended with a 12–7 victory over Ole Miss in the Sugar Bowl, which was the first game between the two Southeastern Conference neighbors in almost twenty years, and only the second in thirty years. Alabama finished #8 in the AP Poll[68][69] In 1964 the Tide went 10–0 in the regular season and won another national championship, but lost 21–17 to Texas in the Orange Bowl.[70][71][72] The Tide ended up sharing the 1964 national title with Arkansas, as the Razorbacks won the Cotton Bowl Classic, and had beaten Texas in Austin.[73] Before 1968, the AP and UPI polls gave out their championships before the bowl games (with the exception of the 1965 season). The AP ceased this practice before the 1968 season, but the UPI continued until 1973.[74][75]

The 1965 Crimson Tide went 9–1–1 and repeated as champions after defeating Nebraska, 39–28, in the Orange Bowl.[76][77] Coming off back-to-back national championship seasons, Bryant's 1966 Alabama team went undefeated, beating a strong Nebraska team, 34–7, in the Sugar Bowl.[78][79] However, Alabama finished third in the AP Poll behind Michigan State and champions Notre Dame, who had previously played to a 10–10 tie in a late regular season game.[80] In a biography of Bryant written by Allen Barra, the author suggests that the major polling services refused to elect Alabama as national champion for a third straight year because of Alabama Governor George Wallace's recent stand against integration.[81]

The 1967 Alabama team was billed as another national championship contender with star quarterback Kenny Stabler returning, but they stumbled out of the gate and tied Florida State, 37–37, at Legion Field.[82] Alabama finished the year #8 at 8–2–1, losing 20–16 in the Cotton Bowl Classic to Texas A&M, coached by former Bryant player and assistant coach Gene Stallings.[83] In 1968 Bryant again could not match his previous successes, as the team finished #17 went 8–3, losing to the Missouri, 35–10, in the Gator Bowl.[84][85]

The 1969 and 1970 teams finished 6–5 and 6–5–1 respectively.[86][87] After these disappointing efforts, many began to wonder if the 57-year-old Bryant was washed up. He himself began feeling the same way and considered either retiring from coaching or leaving college football for the National Football League (NFL).[88]

For years, Bryant was accused of racism[89] for refusing to recruit black players. (He had tried to do so at Kentucky in the late 40s but was denied by then University President, Herman Donovan.)[90] Bryant said that the prevailing social climate and the overwhelming presence of noted segregationist George Wallace in Alabama, first as governor and then as a presidential candidate, did not let him do this. He finally was able to convince the administration to allow him to do so, leading to the recruitment of Wilbur Jackson as Alabama's first black scholarship player who was recruited in 1969 and signed in the Spring of 1970. Junior-college transfer John Mitchell became the first black player for Alabama in 1971 because freshmen, thus Jackson, were not eligible to play at that time. They would both be a credit to the university by their conduct and play, thus widening the door and warming the welcome for many more to follow. By 1973, one-third of the team's starters were black, and Mitchell became the Tide's first black coach that season.[91][92][93][94]

In 1971 Bryant began engineering a comeback. This included abandoning the pro-style offense tailored to departed quarterback Scott Hunter's passing ability for the relatively new wishbone formation.[95] Darrell Royal, the Texas football coach whose assistant, Emory Bellard virtually invented the wishbone, taught Bryant its basics, but Bryant developed successful variations of the wishbone that Royal had never used.[citation needed] The change helped make the remainder of the decade a successful one for the Crimson Tide.[96]

The 1971 Alabama Crimson Tide football team went undefeated in the regular season and rose to #2 in the AP Poll, but were dominated by top-ranked Nebraska 38–6 in the Orange Bowl.[97][98] In the 1972 season, Bryant led Alabama to a 10–0 start before falling to #9 Auburn in the Iron Bowl and #7 Texas in the Cotton Bowl.[99][100]

Bryant's 1973 squad went undefeated in the regular season and split national championships with Notre Dame.[101] Notre Dame later defeated Alabama, 24–23, in the Sugar Bowl.[102] The UPI thereafter moved its final poll until after the bowl games.[103] The Crimson Tide fared very similarly in the 1974 season. The team went undefeated in the regular season but fell to the #9 Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl 13–11.[104][105] The 1975 season started off with a 20–7 setback to the Missouri Tigers. Alabama won every game after that, including the Sugar Bowl over Penn State, to finish 11–1 but finished #3 in the final AP Poll.[106] Alabama went 9–3 in the 1976 season. The Crimson Tide finished the season with a 36–6 victory over #7 UCLA in the Liberty Bowl. Alabama finished #11 in the final AP Poll[107] In the 1977 season, Alabama suffered a 31–24 loss to Nebraska in the second game of the season. Alabama won every game after that including a 35–6 victory over #9 Ohio State in the Sugar Bowl but Notre Dame ended up as National Champions and Alabama was ranked #2.[108][109]

The 1978 Alabama Crimson Tide football team split the national title with USC despite losing to the Trojans in September.[110][111] The Trojans lost later in the year to three-loss Arizona State and drop to number 3. At the end of the year, number 2 Alabama would beat undefeated and top-ranked Penn State in the Sugar Bowl, with the famous late-game goal line stand to preserve the victory.[112]

Bryant won his sixth and final national title in 1979 after a 24–9 Sugar Bowl victory over Arkansas to cap a 12–0 season.[113][114] Bryant led Alabama to a 10–2 record and a #6 ranking in the final AP Poll in the 1980 season.[115] The season ended with a 30–2 victory over #6 Baylor in the Cotton Bowl.[116] In 1981, Bryant led the Crimson Tide to a 9–2–1 record and a #7 ranking in the final AP Poll.[117]

Bryant coached at Alabama for twenty-five years, winning six national titles (1961, 1964, 1965, 1973, 1978, and 1979) and thirteen SEC championships.[118][119] Bryant's win over in-state rival Auburn, coached by former Bryant assistant Pat Dye on November 28, 1981, was Bryant's 315th as a head coach, which was the most of any head coach at that time.[120] His all-time record as a coach was 323–85–17.[121]

Personal life and death

[edit]Bryant was a heavy smoker and drinker for most of his life, and his health began to decline in the late 1970s.[122] He collapsed due to a cardiac episode in 1977 and decided to enter alcohol rehab, but resumed drinking after only a few months of sobriety.[123] Bryant experienced a mild stroke in 1980 that weakened the left side of his body, another cardiac episode in 1981, and was taking a battery of medications in his final years.[124][125]

Shortly before his death, Bryant met with evangelist Robert Schuller on a plane flight and the two talked extensively about religion, which apparently made an impression on the coach.[126]

After a sixth-place SEC finish in the 1982 season that included losses to LSU and Tennessee,[127] each for the first time since 1970, Bryant, who had turned 69 that September, announced his retirement, stating, "This is my school, my alma mater. I love it and I love my players. But in my opinion, they deserved better coaching than they have been getting from me this year."[128] His final loss was to Auburn in Bo Jackson's freshman season.[129] His last game was a 21–15 victory in the Liberty Bowl in Memphis, Tennessee, over the University of Illinois.[130] After the game, Bryant was asked what he planned to do now that he was retired. He replied, "Probably croak in a week."[131]

Four weeks after making that comment, and just one day after passing a routine medical checkup, on January 25, 1983, Bryant checked into Druid City Hospital in Tuscaloosa after experiencing chest pain. A day later, when being prepared for an electrocardiogram, he died after suffering a massive heart attack.[132][133][134]

His personal physician, Dr. William Hill, said that he was amazed that Bryant had been able to coach Alabama to two national championships in what would be the last five years of his life, given the poor state of his health. First news of Bryant's death came from Bert Bank (WTBC Radio Tuscaloosa) and on the NBC Radio Network (anchored by Stan Martyn and reported by Stewart Stogel).[135] On his hand at the time of his death was the only piece of jewelry he ever wore, a gold ring inscribed "Junction Boys".[136] He is interred at Birmingham's Elmwood Cemetery. A month after his death, Bryant was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award, by President Ronald Reagan.[137] A moment of silence was held before Super Bowl XVII, played four days after Bryant's death.[138]

Defamation suit

[edit]In 1962 Bryant filed a libel suit against The Saturday Evening Post for printing an article by Furman Bisher ("College Football Is Going Berserk") that charged him with encouraging his players to engage in brutality in a 1961 game against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.[139] Six months later, the magazine published "The Story of a College Football Fix" that charged Bryant and Georgia Bulldogs athletic director and ex-coach Wally Butts with conspiring to fix their 1962 game together in Alabama's favor.[140] Butts also sued Curtis Publishing Co. for libel.[141] The case was decided in Butts' favor in the US District Court of Northern Georgia in August 1963, but Curtis Publishing appealed to the Supreme Court. As a result of Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts 388 U.S. 130 (1967),[142] Curtis Publishing was ordered to pay $3,060,000 in damages to Butts. The case is considered a landmark case because it established conditions under which a news organization can be held liable for defamation of a "public figure". Bryant reached a separate out-of-court settlement on both of his cases for $300,000 against Curtis Publishing in January 1964.

Honors and awards

[edit]- Inducted into Omicron Delta Kappa at the University of Kentucky in 1949[143]

- Twelve-time Southeastern Conference Coach of the Year[144]

- On October 8, 1988, the Paul W. Bryant Museum opened to the public. The museum chronicles the history of sports at The University of Alabama.[145]

- The portion of 10th Street which runs through the University of Alabama campus was renamed Paul W. Bryant Drive.[146]

- Three-time National Coach of the Year in 1961, 1971, and 1973.[1]: 517 The national coach of the year award was subsequently named the Paul "Bear" Bryant Award in his honor.[147]

- In 1975 Alabama's Denny Stadium was renamed Bryant–Denny Stadium in his honor.[148] Bryant would coach the final seven years of his tenure at the stadium, and is thus one of only four men in Division I-A/FBS to have coached in a stadium named after him. The others are Shug Jordan at Auburn, Bill Snyder at Kansas State and LaVell Edwards at BYU.[citation needed]

- Was named Head Coach of Sports Illustrated's NCAA Football All-Century Team.[149]

- He received 1.5 votes for the Democratic Party Presidential nomination at the extremely contentious 1968 Democratic Convention[150]

- In 1979 Bryant received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement. His Golden Plate was presented by Awards Council member Tom Landry.[151]

- In February 1983 Bryant was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan.[152]

- Bryant was honored with a U.S. postage stamp in 1996.[citation needed]

- Country singer Roger Hallmark recorded a tribute song in his honor.[153]

- Charles Ghigna wrote a poem that appeared in the Birmingham-Post Herald in 1983 as a tribute to Bryant.[citation needed]

- Super Bowl XVII was dedicated to Bryant.[154] A moment of silence was held in his memory during the pregame ceremonies. Some of his former Alabama players were on the rosters of both teams, including Miami Dolphins nose tackle Bob Baumhower and running back Tony Nathan, and Washington Redskins running back Wilbur Jackson.[155][156] Also, at the end of Leslie Easterbrook's performance of the National Anthem, several planes from Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama did the traditional missing-man formation over the Rose Bowl in his memory.[157]

- The extinct shark Cretalamna bryanti was named after Bryant and his family in 2018, due to their contributions to the University of Alabama and McWane Science Center where the type material is held.[158]

Legacy

[edit]Many of Bryant's former players and assistant coaches went on to become head coaches at the collegiate level and in the National Football League. Danny Ford (Clemson, 1981), Howard Schnellenberger (Miami of Florida, 1983), and Gene Stallings (Alabama, 1992), one of the Junction Boys, all won national championships as head coaches for NCAA programs while Joey Jones, Mike Riley, and David Cutcliffe are active head coaches in the NCAA. Charles McClendon, Jerry Claiborne, Sylvester Croom, Jim Owens, Jackie Sherrill, Bill Battle, Bud Moore and Pat Dye were also notable NCAA head coaches.[159] Croom was the SEC's first African-American head coach at Mississippi State from 2004 through 2008.

Super Bowl LV winning NFL head coach Bruce Arians was a running backs coach under Bryant in 1981–82.[160] Arians also served as a successful head coach of the Arizona Cardinals, leading them to just their second ever appearance in the NFC Championship Game in 2015.[161]

Ozzie Newsome, who played for Bryant at Alabama from 1974 to 1977, played professional football for the Cleveland Browns for thirteen seasons (1978–1990), and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1999.[162] Newsome was the general manager of the Cleveland Browns-Baltimore Ravens from 1996 through 2018. Newsome was the GM of the Ravens' Super Bowl XXXV championship team in 2000, and their Super Bowl XLVII championship team in 2012.[163]

Jack Pardee, one of the Junction Boys, played linebacker in the NFL for sixteen seasons with the Los Angeles Rams and Washington Redskins, was a college head coach at the University of Houston, and an NFL head coach with Chicago, Washington, and Houston.[164][165][166]

Bryant was portrayed by Gary Busey in the 1984 film The Bear, by Sonny Shroyer in the 1994 film Forrest Gump, Tom Berenger in the 2002 film The Junction Boys, and Jon Voight in the 2015 film Woodlawn.[167][168][169] Bryant is also mentioned as one of the titular 'Three Great Alabama Icons' in the song of the same name by the Drive-By Truckers on their album Southern Rock Opera.

In a 1980 interview with Time magazine, Bryant admitted that he had been too hard on the Junction Boys and "If I were one of their players, I probably would have quit too."[citation needed]

Head coaching record

[edit]In his 38 seasons as a head coach, Bryant had 37 winning seasons and participated in a total of 29 postseason bowl games, including 24 consecutively at Alabama. He won fifteen bowl games, including eight Sugar Bowls.[170] Bryant still holds the records as the youngest college football head coach to win three hundred games and compile thirty winning seasons.

| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | Coaches# | AP° | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maryland Terrapins (Southern Conference) (1945) | |||||||||

| 1945 | Maryland | 6–2–1 | 3–2 | 5th | |||||

| Maryland: | 6–2–1 | 3–2 | |||||||

| Kentucky Wildcats (Southeastern Conference) (1946–1953) | |||||||||

| 1946 | Kentucky | 7–3 | 2–3 | 8th | |||||

| 1947 | Kentucky | 8–3 | 2–3 | T–9th | W Great Lakes | ||||

| 1948 | Kentucky | 5–3–2 | 1–3–1 | 9th | |||||

| 1949 | Kentucky | 9–3 | 4–1 | 2nd | L Orange | 11 | |||

| 1950 | Kentucky | 11–1 | 5-1 | 1st | W Sugar | 7 | 7 | ||

| 1951 | Kentucky | 8–4 | 3–3 | 5th | W Cotton | 17 | 15 | ||

| 1952 | Kentucky | 5–4–2 | 1–3–2 | 9th | 19 | 20 | |||

| 1953 | Kentucky | 7–2–1 | 4–1–1 | 3rd | 15 | 16 | |||

| Kentucky: | 60–23–5 | 22–18–4 | |||||||

| Texas A&M Aggies (Southwest Conference) (1954–1957) | |||||||||

| 1954 | Texas A&M | 1–9 | 0–6 | 7th | |||||

| 1955 | Texas A&M | 7–2–1 | 4–1–1 | 2nd | 14 | 17 | |||

| 1956 | Texas A&M | 9–0–1 | 6–0 | 1st | 5 | 5 | |||

| 1957 | Texas A&M | 8–3 | 4–2 | 3rd | L Gator | 10 | 9 | ||

| Texas A&M: | 25–14–2 | 14–9–1 | |||||||

| Alabama Crimson Tide (Southeastern Conference) (1958–1982) | |||||||||

| 1958 | Alabama | 5–4–1 | 3–4–1 | T–6th | |||||

| 1959 | Alabama | 7–2–2 | 4–1–2 | 4th | L Liberty | 13 | 10 | ||

| 1960 | Alabama | 8–1–2 | 5–1–1 | 3rd | T Bluebonnet | 10 | 9 | ||

| 1961 | Alabama | 11–0 | 7–0 | T–1st | W Sugar | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1962 | Alabama | 10–1 | 6–1 | 2nd | W Orange | 5 | 5 | ||

| 1963 | Alabama | 9–2 | 6–2 | 2nd | W Sugar | 9 | 8 | ||

| 1964 | Alabama | 10–1 | 8–0 | 1st | L Orange | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1965 | Alabama | 9–1–1 | 6–1–1 | 1st | W Orange | 4 | 1 | ||

| 1966 | Alabama | 11–0 | 6–0 | T–1st | W Sugar | 3 | 3 | ||

| 1967 | Alabama | 8–2–1 | 5–1 | 2nd | L Cotton | 7 | 8 | ||

| 1968 | Alabama | 8–3 | 4–2 | T–3rd | L Gator | 12 | 17 | ||

| 1969 | Alabama | 6–5 | 2–4 | 8th | L Liberty | ||||

| 1970 | Alabama | 6–5–1 | 3–4 | T–7th | T Astro-Bluebonnet | ||||

| 1971 | Alabama | 11–1 | 7–0 | 1st | L Orange | 2 | 4 | ||

| 1972 | Alabama | 10–2 | 7–1 | 1st | L Cotton | 4 | 7 | ||

| 1973 | Alabama | 11–1 | 8–0 | 1st | L Sugar | 1 | 4 | ||

| 1974 | Alabama | 11–1 | 6–0 | 1st | L Orange | 2 | 5 | ||

| 1975 | Alabama | 11–1 | 6–0 | 1st | W Sugar | 3 | 3 | ||

| 1976 | Alabama | 9–3 | 5–2 | 3rd | W Liberty | 9 | 11 | ||

| 1977 | Alabama | 11–1 | 7–0 | 1st | W Sugar | 2 | 2 | ||

| 1978 | Alabama | 11–1 | 6–0 | 1st | W Sugar | 2 | 1 | ||

| 1979 | Alabama | 12–0 | 6–0 | 1st | W Sugar | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1980 | Alabama | 10–2 | 5–1 | T–2nd | W Cotton | 6 | 6 | ||

| 1981 | Alabama | 9–2–1 | 6–0 | T–1st | L Cotton | 6 | 7 | ||

| 1982 | Alabama | 8-4 | 3-3 | T–5th | W Liberty | 17 | |||

| Alabama: | 232–46–9 | 137–28–5 | |||||||

| Total: | 323–85–17 | ||||||||

| National championship Conference title Conference division title or championship game berth | |||||||||

| |||||||||

See also

[edit]- The Bear Bryant Show

- List of presidents of the American Football Coaches Association

- List of college football coaches with 200 wins

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Barra, Allen (2005). The Last Coach: The Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 6. ISBN 9780393059823.

- ^ a b c d Puma, Mike (March 21, 2007). "Bear Bryant 'simply the best there ever was'". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Roberts, Ken (September 10, 2018). "The 'Bear' facts". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Ledbetter, Richard (September 7, 2021). "Fordyce area remembers 'Bear' Bryant". Arkansas Online. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Fordyce on the Cotton Belt". Fordyce on the Cotton Belt. February 26, 2007. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Christopher (March 31, 2020). "Daily Dose of Crimson Tide: The Bear Playing on a Broken Leg". SI.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "SPECIAL REPORT: Paul 'Bear Bryant's timeline". The Tuscaloosa News. February 3, 2018. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Coach Paul Bear Bryant". Paul W. Bryant Museum. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Christopher (May 29, 2020). "Daily Dose of Crimson Tide: The 1934 National Champions". SI.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Christopher (April 11, 2015). "25 interesting facts about former Alabama legend Don Hutson". Saturday Down South. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Don Hutson Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Draft, College". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on June 22, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1936 NFL Draft Listing". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "Former 'Bama Star Takes Union Coaching Job". Nashville Banner. February 4, 1936. p. 7. Retrieved April 11, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Palmeri, Allen. "Remembering the Titans". UU.edu. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Burton, Larry (August 24, 2019). "The men before the Bear that started the story of Alabama football glory – Touchdown Alabama – Alabama Football". Touchdown Alabama. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Frank Thomas College Coaching Records, Awards and Leaderboards". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ ""Bear" Bryant Declines Grid Post At V. M. I." Hope Star. January 14, 1937. p. 4. Retrieved April 11, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Bear' Bryant Signs Two-Year Contract As 'Bama Assistant". Birmingham Post-Herald. January 14, 1937. p. 10. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Traughber, Bill (September 27, 2006). "CHC- Bear Bryant Was A Commodore". Vanderbilt University Athletics – Official Athletics Website. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bear Bryant, Former Tide Star, Will Help Sanders At Vanderbilt". The Knoxville Journal. March 23, 1940. p. 7. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Bear Bryant Named No. 1 Assistant To Sanders At Vanderbilt". The Birmingham News. March 23, 1940. p. 8. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Dunnavant, Keith (2005). Coach: The Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant. Macmillan. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-3123-4876-2.

- ^ Hutchinson, Andrew (September 26, 2013). "Fate Keeps Bear Bryant From Coaching at Arkansas". The Arkansas Traveler. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bowl bid for Tide hinges on Pre-Flight tilt result". The Tuscaloosa News. November 27, 1942. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2012 – via Google News.

- ^ "Alabama Closes Season With Naval Pre-Flight Team Here Saturday". The Birmingham News. November 23, 1942. p. 14. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Bennett, BJ. "Bear Bryant's Living Legacy". Southern Pigskin. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Tomberlin, Jason (October 21, 2009). "Bear Bryant in Chapel Hill". North Carolina Miscellany. UNC University Libraries. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Bear Bryant Line Coach At Carolina". Nashville Banner. August 18, 1944. p. 16. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ Donahue, Ben (April 21, 2021). "The Life And Career Of Otto Graham (Complete Story)". Browns Nation. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Browning, Al (2001). I Remember Paul "Bear" Bryant. Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 100–101. ISBN 1-58182-159-X.

- ^ Shapiro, Leonard (November 27, 1981). "BRYANT". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1945 Maryland Terrapins Stats". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Phillips, B. J. (September 29, 1980). "Football's Supercoach". Time. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "Kentucky Wildcats Bowls". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1950 Southeastern Conference Year Summary". Sports Reference. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Sugar Bowl – Oklahoma vs Kentucky Box Score, January 1, 1951". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "FBS Football Championship History". NCAA.com. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Recognized National Championships by Year". cfbdatawarehouse.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ a b "Kentucky Wildcats AP Poll History". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Puma, Mike. "ESPN Classic – Bear Bryant 'simply the best there ever was'". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bear Bryant and Rupp". Big Blue History. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ "The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame: C.M. Newton". HoopHall.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Hale, Jon (October 3, 2018). "A look back at the day Paul 'Bear' Bryant left Kentucky for Texas A&M". The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Croome, Richard (April 9, 2014). "Aggies recognize longtime Alabama Coach Bear Bryant for time at Texas A&M". The Eagle. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1954 Texas A&M Aggies Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Clark, Rob (August 15, 2014). "Survivors of A&M Coach 'Bear' Bryant's grueling training camp reunite in Junction on 60th anniversary". The Eagle. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Texas A&M at Texas Box Score, November 29, 1956". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1956 Southwest Conference Year Summary". Sports Reference. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1957 Heisman Trophy Voting". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1957 Texas A&M Aggies Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Roberts, Randy (September 13, 2013). "Bear Bryant: When the Legend Left for Alabama". WSJ. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Barra, Allen (Winter 2006). "Bear Bryant's Biggest Score". American Legacy: 58–64. Archived from the original on May 19, 2010.

- ^ Moore, Tamika (January 26, 2016). "Coach Paul "Bear" Bryant quotes on winning, life". AL.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Estes, Gentry (May 12, 2008). "Remembering Bear Bryant's first game as Alabama coach ..." AL.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1955 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1956 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1957 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1958 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Morton, Jason (August 16, 2008). "Bear's '58 team reunites, recalls Tide's turning point to success". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Iron Bowl history: Scores". AL.com. November 26, 2010. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Alabama Crimson Tide Bowls". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1959 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1960 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1961 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Christopher (February 3, 2022). "Throwback Thursday: 1961, Bear Bryant's First National Championship". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Burton, Larry (July 27, 2015). "Joe Namath Responded Well To Coach Bryant's Tough Love". Touchdown Alabama. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1962 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1963 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Football History vs University of Alabama". Ole Miss Athletics. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1964 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Nicandros, Dino (December 8, 2009). "A Look Back at the 1965 Orange Bowl: Alabama vs. Texas". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1964 College Football Summary". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 25, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Gribble, Andrew (October 10, 2014). "Arkansas to honor 1964 national championship team vs. Alabama, which also claims 1964 national title". AL.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Molski, Max (January 3, 2022). "The history of college football championship games". RSN. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "A Concise Summary Of College Football Major Bowl Game History". The Sports Notebook. June 23, 2018. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1965 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on August 17, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Molski, Max (January 5, 2023). "History of Repeat Champions in College Football". NBC Connecticut. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1966 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1966 College Football Polls". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Shepkowski, Nick (April 20, 2022). "Remembering college football's most famous tie". Fighting Irish Wire. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Barra, Allen (2005). The Last Coach: A Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393059823.

- ^ "1967 Flashback: Alabama 37, Florida State 37". University of Alabama Athletics. September 26, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1967 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1968 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Henry, Jim (December 4, 2014). "Roll Mizzou: Tigers whip heavily favored Alabama in 1968 Gator Bowl". Joplin Globe. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1969 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1970 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Sims, Alex (April 24, 2013). "How Bear Bryant Became the Branch Rickey of Alabama Football". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Doyle, Andrew (March 1996). "Bear Bryant: Symbol for an Embattled South". Colby Quarterly. 32 (1): 80, 83. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Miller, Patrick (2002). The Sporting World of the Modern South. University of Illinois Press. p. 272.

- ^ Durso, Joseph (January 27, 1983). "Bear Bryant Is Dead at 69; Won a Record 323 Games". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Harwell, Hoyt (June 6, 1983). "Bryant and blacks: Both had to wait". The Huntsville Times. Huntsville, Alabama. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Barra, Allen (November 15, 2013). "The Integration of College Football Didn't Happen in One Game". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Puma, Mike. "Bear Bryant 'simply the best there ever was'". SportsCentury. ESPN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Deas, Tommy (September 11, 2013). "The wishbone". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Scarbinsky, Kevin (May 16, 2017). "Our All-Bryant offense could be two teams, before and after the wishbone". AL.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1971 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Jenkins, Dan (January 10, 1972). "All Yours, Nebraska". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1972 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Stephen M. (November 27, 2020). "A look at 1972 Iron Bowl: Auburn pulls victory from Tide with special teams". Touchdown Alabama. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1973 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Kausler Jr., Don (December 11, 2012). "Alabama-Notre Dame: Epic 1973 Sugar Bowl lived up to its billing (Part I)". AL.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Penner, Mike (November 24, 1998). "Polls Apart". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1974 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Schexnayder, C. J. (December 13, 2012). "Alabama vs Notre Dame – The 1975 Orange Bowl". Roll 'Bama Roll. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1975 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1976 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1977 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1977 College Football Summary". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1978 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Zemek, Matt (May 23, 2020). "USC and the SEC: The 1978 USC-Alabama poll debate". Trojans Wire. Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Higgins, Ron (April 14, 2022). "Remembering the 1979 Goal Line Stand". Sugar Bowl. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1979 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "CHAMPIONSHIP CAPSULES: 'Bear' Bryant's six national titles". The Tuscaloosa News. February 3, 2018. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1980 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Trott, William C. (January 1, 1981). "The Baylor Bears came into Thursday's Cotton Bowl with..." UPI. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1981 Alabama Crimson Tide Schedule and Results". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Staats, Wayne (January 3, 2023). "College football coaches with the most national championships". NCAA.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Rothschild, Richard (January 8, 2016). "Alabama football: Comparing Nick Saban, Bear Bryant's careers". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Stephenson, Creg (November 26, 2015). "Check out vintage photos from the 1981 Iron Bowl". AL.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Durso, Joseph (January 27, 1983). "BEAR BRYANT IS DEAD AT 69; WON A RECORD 323 GAMES". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Pinak, Patrick (January 26, 2023). "The Strange Coincidence of Bear Bryant's Death 40 Years Ago". FanBuzz. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Hall, Spencer (June 3, 2011). "College Coaches, Drinking, And The Two Men At The Rail". SBNation.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Barnes, Bart (January 28, 1983). "Cardiologist on Bryant: History of Heart Failure". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Rawls Jr, Wendell (January 28, 1983). "BRYANT'S DOCTOR TELLS OF LENGTHY ILLNESS". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Garrison, Greg (April 2, 2015). "Did Bear Bryant go to heaven? Robert Schuller said so". AL.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1982 Southeastern Conference Year Summary". Sports Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Elderkin, Phil (December 24, 1982). "Legendary Bear Bryant will be a tough act to follow". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Stephenson, Creg (November 24, 2022). "How 1982 Iron Bowl transformed the Auburn-Alabama rivalry". AL.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Goodbread, Chase (December 22, 2022). "How Alabama diffused Illinois' attempt to spoil 'Bear' Bryant's final game". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Callahan, Tom (February 7, 1983). "Tears Fall on Alabama". Time (subscription required). Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Day, Dre (January 26, 2022). "On This Day We Said Goodbye to A Legend: Rest Easy Paul "Bear" Bryant". 105.1 The Block. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Timeline: Alabama football legend Paul 'Bear' Bryant's life, 40 years after his death". The Tuscaloosa News. January 26, 2023. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Mark (January 27, 1983). "Bear Bryant dies of heart attack". UPI. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bear Bryant: 25 Years – Techography". Techography. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009.

- ^ Puma, Mike (November 19, 2003). "ESPN Classic – Goal-line stand propels Bryant's Tide to title". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom". Reagan Library. February 23, 1983. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Sperrazza, Casey (August 23, 2015). "Alabama is More than a Football school. Thirty People Who Got a Start at Alabama". Bama Hammer. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023 – via FanSided.

- ^ Bisher, Furman (October 20, 1962). "College Football is Going Berserk" (PDF). The Saturday Evening Post. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ Graham, Frank Jr. (March 23, 1963). "The Story of a College Football Fix" (PDF). The Saturday Evening Post. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ "Paul Bryant Facts". yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ 388 U.S. 130 (1967)

- ^ Baker, Sara (February 27, 2017). "Members of Campus Community Honored at Omicron Delta Kappa Leadership Awards Ceremony". UKNow. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Lay, Ken (November 3, 2021). "A look back at former Kentucky head coach Bear Bryant". Vols Wire. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Paul W Bryant Museum – University of Alabama". Paul W Bryant Museum – University of Alabama. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Berry, Chad (January 25, 2004). "Streets of Tuscaloosa: Bryant Drive". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Final Title of the Season: The Paul "Bear" Bryant Awards". American Heart Association – Houston Office website. American Heart Association, Inc. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Bryant-Denny Stadium – The University of Alabama". Paul W Bryant Museum. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Maisel, Ivan (August 16, 1999). "SI's NCAA Football All-Century Team". Sports Illustrated. ISSN 0038-822X. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Buchanan, Jim (July 25, 2018). "A Democratic convention in chaos cast votes for Moore". The Sylva Herald. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ "Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom". Reagan Library. February 23, 1983. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Moore, Addie (September 4, 2021). "These 5 Country Songs Laud College Football Great Bear Bryant". Wide Open Country. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Mark (December 17, 2016). "Ten facts about Paul 'Bear' Bryant's career". The Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "1982 Miami Dolphins Rosters, Stats, Schedule, Team Draftees". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "1982 Washington Redskins Rosters, Stats, Schedule, Team Draftees". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Solomon, Jon (September 11, 2013). "100 years of Bear Bryant; 100 facts you may not know". AL.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Ebersole, J.A.; Ehret, D.J. (2018). "A new species of Cretalamna sensu stricto (Lamniformes, Otodontidae) from the Late Cretaceous (Santonian-Campanian) of Alabama, USA". PeerJ. 6: e4229. doi:10.7717/peerj.4229. PMC 5764036. PMID 29333348.

- ^ Weisband, Brett (March 30, 2015). "Bear Bryant's coaching tree". Saturday Down South. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Cooper, Jon (May 23, 2018). "Bruce Arians tells story of time he stood up to Bear Bryant at Alabama". Saturday Down South. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ Weinfuss, Josh (July 19, 2016). "Bruce Arians didn't see Cardinals' blowout in NFC title game coming 'in a million years'". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ozzie Newsome College Stats, School, Draft, Gamelog, Splits". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Ozzie Newsome Football Executive Record". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Jack Pardee Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Draft, College". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Jack Pardee College Stats, School, Draft, Gamelog, Splits". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Jack Pardee Record, Statistics, and Category Ranks". Pro Football Reference. Archived from the original on January 12, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Casagrande, Michael (June 20, 2014). "Controversial Bear Bryant movie has small cult following 30 years after box office bomb". AL.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Flanagan, Ben (June 27, 2019). "Sonny Shroyer on playing Bear Bryant in 'Forrest Gump'". AL.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Garrison, Greg (August 30, 2015). "Jon Voight talks about playing Bear Bryant in 'Woodlawn'". AL.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "Bear Bryant College Coaching Records, Awards and Leaderboards". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Keith Dunnavant, Coach: The Life of Paul "Bear" Bryant (New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2005).

- Paul W. Bryant with John Underwood, Bear: The Hard Life and Good Times of Alabama's Coach Bryant (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974).

- Mickey Herskowitz, The Legend of Bear Bryant, (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1993).

- Jim Dent, ''The Junction Boys: How Ten Days in Hell with Bear Bryant Forged a Championship Team (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999).

- Tom Stoddard, Turnaround: Bear Bryant's First Year at Alabama (Montgomery, Alabama: Black Belt Press, 2000).

- Randy Roberts and Ed Krzemienski, Rising Tide: Bear Bryant, Joe Namath, and Dixie's Last Quarter (New York: Twelve, Hachette Book Group, 2013).

- James Kirby, Fumble: Bear Bryant, Wally Butts, and the Great College Football Scandal (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanavich, 1986).

- Albert Figone, Cheating the Spread: Gamblers, Point Shavers and Game Fixers in College Football and Basketball (University of Illinois Press, 2012).

- Furman Bisher, "College Football is Going Berserk: A Game Ruled by Brute Force Needs a Housecleaning", Saturday Evening Post, October 20, 1962.

- Frank Graham Jr. "The Story of a College Football Fix", Saturday Evening Post, March 23, 1963.

- John David Briley. 2006. Career in Crisis : Paul "Bear" Bryant And the 1971 Season of Change. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

External links

[edit]- Paul W. Bryant Museum

- Bear Bryant at the College Football Hall of Fame

- Coaching statistics at Sports Reference

- "Paul 'Bear' Bryant" Archived June 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Digitized speeches and photographs of Coach Bryant from the University Libraries Division of Special Collections, The University of Alabama

- Bear Bryant at Find a Grave

- 1913 births

- 1983 deaths

- American football ends

- Alabama Crimson Tide athletic directors

- Alabama Crimson Tide football coaches

- Alabama Crimson Tide football players

- Burials at Elmwood Cemetery (Birmingham, Alabama)

- Georgia Pre-Flight Skycrackers football coaches

- Kentucky Wildcats football coaches

- Maryland Terrapins football coaches

- North Carolina Pre-Flight Cloudbusters football coaches

- Texas A&M Aggies athletic directors

- Texas A&M Aggies football coaches

- Union University Bulldogs football coaches

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- People from Cleveland County, Arkansas

- Coaches of American football from Arkansas

- Players of American football from Arkansas

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- United States Navy officers

- Vanderbilt Commodores football coaches

- Presidents of the American Football Coaches Association