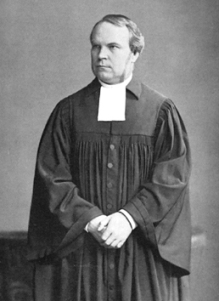

Adolf Stoecker

Adolf Stoecker (December 11, 1835 – February 2, 1909) was a German court chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, a politician, leading antisemite, and a Lutheran theologian who founded the Christian Social Party to lure members away from the Social Democratic Workers' Party.

Early life

[edit]Stoecker was born in Halberstadt, Province of Saxony, in the Kingdom of Prussia. Stoecker's father was a blacksmith turned prison guard, and despite his poverty, Stoecker was able to attend university, which was unusual for a working-class man in the 19th century.[1] An energetic and hardworking Protestant pastor who wrote widely on various social and political issues, Stoecker had a charismatic personality which made him one of Germany's best loved and most respected Lutheran clergyman.[2] As a theology student at the University of Halberstadt, Stoecker was already known as the "second Luther" as his writings and speeches defending the Lutheran faith were considered outstanding.[2]

After his ordination as a minister, Stoecker joined the Prussian Army as a chaplain.[1] Stoecker came to national attention after delivering a sermon after the Siege of Metz in 1870, where he argued that Prussia's victories over France were the doing of God, and in 1874, Emperor Wilhelm I, who had been moved by Stoecker's sermons, had him appointed court chaplain in Berlin.[2] Stoecker's position as a court chaplain gave him more power and prominence than his title of pastor would indicate, as everything Stoecker said was seen as expressing the opinion of Wilhelm.[2] As early as 1875, Stoecker began to attack Jews in racial terms in his sermons.[1] As a good Lutheran, Stoecker was impressed with Martin Luther's 1543 book On the Jews and their Lies, and throughout his life, Stoecker always held that to be a good Christian meant hating the Jews.[3]

Founding of CSP

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

Besides working as a court chaplain, Stoecker also served as the head of a church mission in central Berlin that offered aid to the poorest families of the city.[2] Stoecker was shocked by the extent to which the German poor and working classes had become estranged from Lutheranism and later wrote with horror: "During the years 1874–78, eighty percent of all marriages took place outside the church and forty-five percent of all children were not baptized".[2] Furthermore, the staunchly-conservative Stoecker was worried about the way that the poor and the working class were voting for the "godless" Social Democratic Party (SPD), and to counter the growth of the SPD, he founded the Christian Social Worker's Party (CSP) in 1878.[2] Though strongly critical of capitalism and demanding some social reforms like an income tax and reducing working hours, Stoecker was hostile to unions and supported the existing social structure in which the Junkers dominated Prussian society.[2] Stoecker was not a Junker, but he always had the most profound admiration for them.[2] The purpose of the CSP was to win over the working classes to a Christian conservatism in which ordinary people would learn to accept that God had created an ordered society with the Junkers on top, and that to challenge the ordered society was to challenge God.[2] Stoecker believed that the capitalist system alienated workers from the proper, God-intended course, and what was needed were social reforms to hold off revolution.[2]

Through Stoecker advocated social reforms, the main emphasis of the CSP was on winning workers over to loyalty to "the throne and altar", as Stoecker argued that misery of the workers was caused by a materialistic, atheist world view that had torn the working class from its proper reverence for God and the social order created. The message was rejected by most German workers as not addressing their main concerns.[4] The German working class mostly wanted a higher standard of living and democracy, not to be told that it was their duty as Christians to accept their lot. Stoecker's hostility to unions and strikes limited his appeal to the working class.[2] Stoecker called unions "the threatening danger which moves through our time like a flood between weak dykes".[2] Stoecker believed that workers should not fight for higher wages and improve working conditions through strikes, but should deferentially ask "throne and altar" to improve working conditions and wages, a message that strongly limited his appeal to the working class.[2] Stoecker's platform sounded very left-wing with its demand for an income tax, banning children and married women from working, making Sunday a holiday; subsidies for widows and those too injured to work, taxes on luxury goods and a government-supported health system for all.[5] However, at same time, Stoecker's platform called for bringing unions under state control, as Stoecker viewed the purpose of unions was to teach their members to be loyal to "throne and altar", not to improve the lives of their members.[6]

When Stoecker founded the Christian Social Party on 3 January 1878, he declared in his speech announcing his party:

"I have in mind a peaceful organization of labor and the workers.... It is your misfortune, gentleman, that you only think of your Social State and scornfully reject the hand extended to you for reform and help; that you insist on saying "we will not settle for anything less than the Social State". This way makes you enemies of the other social classes. Yes, gentleman, you hate the Fatherland! Your press shockingly reflects this hatred... you also hate Christianity, you hate the gospel of God's mercy. They [the Social Democrats] teach you not to be believe. They teach you atheism and these false prophets".[7]

Stoecker followed his speech by presenting a former tailor who had been imprisoned for fraud, Emil Grüneberg, whom Stoecker had met while he was in prison, who proceeded to give a violently anti-Socialist speech.[7] The American historian Harold Green commented that Stoecker associating with a disreputable individual like Grüneberg, a swindler and blackmailer showed the "demagogic and unsavory" character of Stoecker, who for his all self-righteousness often associated with disreputable people.[7] Much to Stoecker's fury, a group of Social Democrats, led by Johann Most, showed up to hijack the meeting as Most gave a speech denouncing the Lutheran church for being subservient to the state and declared that only the Social Democrats represented the working class, which prompted loud cheers from the working-class audience.[7] Most led the audience out of the meeting hall, all behind him, while Stoecker was left fuming, as his would be supporters had been taken away by Most.[7] The German chancellor, Prince Otto von Bismarck, brought the first of the Anti-Socialist Laws later in 1878 with the aim of crushing the SPD, and Stoecker's foray into politics was secretly supported by the government, which hoped that Stoecker might be able to win the working class from the Social Democrats.[8]

Anti-Semitic agitator

[edit]In 1879, Stoecker gave speeches blaming all of Germany's problems on the Jewish minority.[8] In his speech "Our Demands on Modern Jewry", delivered in Berlin on 19 September 1879, Stoecker in the words of the American historian Richard Levy "put antisemitism on the map in Germany", as his status as one of Germany most respected and best loved Lutheran clergymen made hatred for the Jews eminently respectable in a way that it never had been before.[4] It was only after Stoecker started to attack the Jews that the meetings of the CSP began to be well attended, but most of Stoecker's followers came from the Mittelstand (lower middle class), rather than the working class and the poor.[8] In September 1879, Stoecker's speech "Our Demands on Modern Jewry" caused a sensation and attracted much media attention, as it was widely assumed that Stoecker was speaking on behalf of Emperor Wilhelm I when he blamed all of Germany's problems on "Jewish capital" and the "Jewish press".[8] Stoecker, in particular, complained that 45,000 Jews living in Berlin were "too large a figure" and that Germany was taking in far too many poor Jewish immigrants from Russia and Romania. He argued that Jewish immigrants from the Russian empire and Romania should be "sunk on the high seas", rather be allowed to settle in Germany.[9] As early as 17 October 1879, the Board of Trustees of the Jewish community in Berlin had complained to the Prussian Ministry of the Interior that Stoecker should be silenced as his hate speeches were inciting violence against Jews, a request that was refused.[9] Stoecker's denunciations of the changes wrought by industrialization and urbanization appealed to the lower middle class, as he offered up an idealized, nostalgic vision of an ordered, rural society, where local craftsmen and small merchants did not have to compete with factories and large stores, of a simpler, better time now sadly gone.[10] Stoecker's critique of modernity and of the capitalist system under the guise of very nationalist and anti-Semitic message appealed to the Mittelstand, which was suffering very badly from the economic changes caused by the Industrial Revolution and felt their interests to be ignored by all of the existing parties.[10]

Traditionally, for over 1000 years, Jews were despised social outcasts, a people living in poverty and seen as accursed forever, and Jewish emancipation in Prussia in 1869 had been followed by the rise of a number of poor Jewish families to the middle class.[4] At the same time that Jews were joining the middle class, the fortunes of the Mittelstand had gone into decline, and Stoecker's anti-Semitic speeches appealed to what he called the "little people", as the Mittelstand's men and women who felt it was unfair and unjust that the traditionally-despised Jews were getting ahead both socially and economically while they were falling behind.[4] Jews were seen as outsiders in Imperial Germany, and the socio-economic success of the Jews seemed to be turning the traditional social order upside down just as at the same moment that many Mittelstand families were sinking into poverty.[4] Stoecker's speech "Our Demands on Modern Jewry" was full of a sense of victimization, as he accused Jews of behaving with outrageous arrogance to Germans, and he demanded that newly middle class Jewish families should "show respect" to the Germans.[11] Levy wrote that Stoecker understood the resentments and fears, the sense of victimization held by the "little people" of the mittelstand, as he explained that the "Jewish Press" and "Jewish capital" caused all their problems.[11] Typical of the sense of victimization that Stoecker encouraged was a speech from 1879 where he declared:

"If modern Jewry continues to use the power of capital and the power of the press to bring misfortune to the nation, a final catastrophe is unavoidable. Israel must renounce its ambition to become master of Germany. It should renounce its arrogant claim that Judaism is the religion of the future, when it is so clearly of the past...Every sensible person must realize the rule of this Semitic mentality means not only our spiritual, but also our economic impoverishment".[12]

Though Stoecker did not call for violence, he implied that violence would be acceptable if the Jews did not begin to "show respect" to the Germans, which they allegedly did not.[4] Stoecker fed the sense of victimization as with his speech "The Lousy Press" in which he argued to his supporters that the media was controlled by rich Jewish capitalists who disliked people like them and that the economic decline of the Mittelstand was being ignored because of the "lousy press".[13] Stoecker's speeches usually consisted of reading various out-of-context statements from Social Democratic newspapers, to be followed by statements like "Gentleman, that was a wish for murder!", "Gentleman that was truly murder!", or "That was mass murder!".[13] As the crowd would become more and more angry, Stoecker would present his usual caveat, "Don't think I present all this out of hatred. I don't hate anyone!", which the American historian Jeffery Telman observed was "highly ironic" since Stoecker would whip up his supporters into a state of fury.[13]

Though Stoecker professed to be motivated only by "Christian love", he always blamed anti-Semitism on the Jews and stated in a speech: "Already a hatred for the Jews—which the Evangelical Church resists—begins to blaze up here and there. If modern Judaism continues, as it thus far has, to use the force of capital as well the power of the press, to ruin the nation, it will be impossible to avoid a catastrophe in the end".[14] Though Stoecker professed to be speaking with "full Christian love" for the Jews, it was always counterbalanced with a violent attack on Judaism as when he warned in a speech that one should not allow "Jewish newspapers to attack our belief and for the Jewish spirit of Mammonism to sully our people".[15] As one of the first leaders of the Völkisch movement, Stoecker attacked the Jews as a "race" and said in a speech at the Prussian Landtag in 1879 that all Jews were "parasites" and "leeches", an "alien drop in our blood" and stated that battle between Germans vs. Jews was one of "race against race", as the Jews were "a nation unto themselves" with nothing in common with Germans, but instead were linked to the other Jewish communities around the world as "one mass of exploiters".[16]

Though Stoecker was very vague about the exact solution to the "Jewish Question" he wanted, in one of his pamphlets, he wrote "the ancient contradiction between Aryans and the Semites... can only end with the extermination of one of them" and it was the responsibility of "the Germanentum...to settle once and for all with the Semites".[17] Like everybody else in the völkisch movement, Stoecker was deeply influenced by the claim of the French writer Arthur de Gobineau that there was an ancient Aryan master race responsible for everything good in the world, of which the modern Germans were the best representatives, but Stoecker rejected Gobineau's conclusion that the Aryan race was doomed.[5] Stoecker seems to have regarded Jews as both a race and a religion as he stated in a speech:

"Race is, without a doubt, an important element in the Jewish Question. The Semitic-Punic type is, in all areas, in work as well in profit, in business as well in earnings, in the life of the state as well in worldview, in its spiritual as well as its ethical effects—so different from the Germanic morals and philosophy of life, that reconciliation or amalgamation is impossible, unless it takes the form of a sincere rebirth from the depths of the conscience from the upright Israelites".[18]

In another speech, Stoecker stated:

"The Jewish Question, insofar as it is a religious question, belongs to science and the missionaries; as a racial question, it belongs anthropology and history. In the form of which this question appears before our eyes in public life, it is highly complicated social-ethical, political-economic phenomena.... This question has arisen and developed—under the influence of religion and race—differently in the Middle Ages from how it is today, different also in contemporary Russia from how it is with us. But the Jewish Question—always and everywhere—has to do with economic exploitation and the ethical disruption of the peoples among who the Jews have lived".[19]

In another speech, Stoecker linked his Christian work with his political work, saying:

"I found Berlin in the hands of the Progressives—who were hostile to the Church—and the Social Democrats—who were hostile to God; Judaism ruled in both parties. The Reich's capital city was in danger of being de-Christanized and de-Germanized. Christianity was dead as a public force; with it went loyalty to the King and love of the Fatherland. It seemed as if the great war [with France] had been fought so that Judaism could rule in Berlin.... It was like the end of the world. Unrighteousness had won the upper hand; love had turned cold".[20]

Opposition from the Crown Prince and Crown Princess

[edit]Together with another völkisch leader, the historian Heinrich von Treitschke, Stoecker launched the Antisemitic Petition in 1880 that was signed by a quarter of million Germans asking for Jewish immigration to Germany to be banned, Jews to be forbidden to vote and hold public office and Jews to be forbidden to work as teachers or attend universities.[21] The ultimate intention of Stoecker and Treitschke was the disemancipation of German Jews, and the Antisemitic Petition was only the planned first step. In response to the Antisemitic Petition, the Crown Prince Frederich attacked anti-Semitism in an 1880 speech as a "shameful blot on our time" and said on behalf of himself and his wife Victoria with clear reference to Stoecker: "We are ashamed of the Judenhetze which has broken all bounds of decency in Berlin, but which seems to flourish under the protection of court clerics".[21]

The British-born Crown Princess Victoria in a public letter said that Stoecker belonged in a lunatic asylum because everything he had to say reflected an unbalanced mind.[21] Victoria wrote that she was ashamed of her adopted country as men like Stoecker and Treitschke "behave so hatefully towards people of a different faith and another who have become an integral part (and by no means the worse) of our nation!"[21] The Crown Prince of Prussia, Frederich, delivered a speech at a Berlin synagogue, where he called Stoecker the "shame of the century" and promised that if he became Emperor, he would fire Stoecker as court chaplain, leading to enthusiastic cheers from the audience.[22]

The Bleichröder affair

[edit]In 1880, Stoecker attacked the Chancellor, Prince Otto von Bismarck indirectly when he singled out Gerson von Bleichröder, the Orthodox Jew who served as Bismarck's banker, though not by name as the author of the problem of poverty in Germany.[23] In a speech delivered on 11 June 1880, Stoecker attacked an unnamed Orthodox Jewish banker to powerful people, by which he clearly meant Bleichröder, who he claimed had too much power and wealth.[23] Stoecker stated the solution to poverty was to confiscate the wealth from rich Jews, rather than have an "impoverished" Church minister to the poor, and said that the banker was "a capitalist with more money than all the evangelical clergy taken together".[24] Bleichröder complained to Bismarck that Stoecker's attack might lead him to leave Germany for another nation that would be more welcoming to him, and as Bleichröder's skills at banking had made both him and Bismarck very rich men, Bismarck was worried about losing his banker.[24] Bismarck saw the attack on Bleichröder as an attack on himself and seriously considered banning Stoecker from speaking, but he declined as Stoecker was too popular and his position as court chaplain made him unassailable as he had the Emperor's support.[23] Bismarck complained that Stoecker "was attacking the wrong Jews, the rich ones committed to the status quo rather than the propertyless Jews... who had nothing to lose and therefore joined every opposition movement".[3]

In December 1880, under pressure from Bismarck, Wilhelm I formally admonished Stoecker for his attack on Bleichröder in a letter for having "incited rather than calmed greed, by having drawn attention to big individual fortunes and by proposing reforms that in light of the government's program were too extravagant".[24] The American historian Harold Green noted that Bismarck seemed to have a problem with Stoecker's anti-Semitism only when it was directed against Bleichröder, and as long as Stoecker attacked Jews in general, instead of singling out Bleichröder, Bismarck did not have an issue with Stoecker.[24] The letter from the emperor only attracted more attention to Stoecker, and more people continued to join the CSP.[24] Teachers and army officers were overrepresented in the CSP, and in 1881, Stoecker renamed his party the Christian Social Party, as very few workers had joined his movement, and the Worker's part of the title was offputting to his mostly lower middle-class supporters.[24] Bismarck ended his support for Stoecker in 1881 after the "Bleichröder affair" and because Stoecker had failed to win the working class from the SPD, instead attracting support from an already-conservative Mittelstand.[24]

In 1882, Stoecker attended the world's first anti-Semitic international congress in Dresden.[1] Stoecker was condemned most forcefully by Frederich, the Crown Prince of Prussia and his British-born wife Victoria. In 1882, Wilhelm agreed to receive Stoecker and other leaders of the Berlin movement, which as an enthusiastic Stoecker reported:

"His Imperial Majesty, the Kaiser agreed to receive delegates from the Berlin movement on the eve of his birthday, something that had never happened before in the case of a political party. I had the honor to deliver a speech...[after the address] the Kaiser aptly replied that there had been very strange developments during the past year; that both the most autocratic monarch in the world, the Russian Emperor and the least authoritarian President of a Republic, the American Chief of State had been assassinated, that authority was in terrible danger everywhere and it necessary to be fully aware of this."[25]

In 1883, Stoecker attended a conference of evangelical Protestants in London, where the Lord Mayor forbade the "second Luther" from speaking at the Mansion House under the grounds his speech was going to be a threat to public order. When Stoecker spoke at an alternative venue, Social Democratic emigres showed up to disturb the speech, forcing Stoecker to flee from the stage and to sneak out via the backdoor, behavior that led many to condemn the "second Luther" as a coward.[26]

The Bäcker case

[edit]In 1884, Stoecker sued a Jewish newspaper publisher, Heinrich Bäcker for libel after the latter had run an article, "Court Chaplain, Reichstag Candidate and Liar".[26] Because Stoecker was a court chaplain, Bäcker was prosecuted by the Prussian state for libelling a public official but he waged such a vigorous defense that his claim that Stoecker was a dishonest man was true that he effectively put Stoecker on trial.[27] As a witness, Stoecker was humiliated on a daily basis, as Bäcker's lawyers presented many examples from his speeches of him telling lies and having committed perjury in another court case when he testified that he never seen a Social Democrat named Ewald before, despite having repeatedly spoken with him during Reichstag sessions.[28] As Stoecker was repeatedly challenged by Bäcker's lawyers about various lies that he had told and contradictory statements that he had made over the years, Stoecker was put on the defensive more and more as he attempted to explain that he did not mean what he had said or he could not remember saying what he had said, making him appear dishonest and shifty.[29] Stoecker's reputation was so badly damaged that despite the fact it was Bäcker who was on trial, the judge, in a revealing Freudian slip, opened a session of the court with the remark: "I hereby reopen the proceedings against the defendant Stoecker", only to be reminded that it was Bäcker who was on trial.[30] The libel case attracted much media attention, and though Stoecker won the case, the judge gave Bäcker the lightest possible sentence of three weeks in prison, under the grounds that the publisher had been persistently attacked by Stoecker.[26] Bäcker won a moral victory, as even through the court had convicted him, Stoecker had been exposed on the stand as a man who was caught up in so many lies as to destroy his reputation.[31] The judges had given a convoluted and tortured ruling in the libel trial that seemed to suggest that they wanted to acquit Bäcker but had convicted him only because to acquit Bäcker would confirm his claims against Stoecker, which would damage the prestige of the monarchy, as Stoecker was the court chaplain.[32]

By 1885, Emperor Wilhelm, though an anti-Semite himself, had wanted to fire Stoecker, who had become a liability to the monarchy after the Bäcker libel case but kept him only after his grandson, Prince Wilhelm (the future Wilhelm II) had written him a letter on 5 August 1885 praising Stoecker and claiming that had been attacked unjustly by the "Jewish press".[22] Prince Wilhelm wrote that to dismiss Stoecker would be to strengthen the Social Democratic and the Progressive parties, who the prince claimed to be both controlled by the Jews.[22] Prince Wilhlem called Stoecker the victim of the "ghastly and infamous slanders of the damned Jewish press" and wrote "poor Stoecker" had been "covered with insults, slanders and defamation". He went on, "Now, after the judgement of the court, which is unfortunately far too much under Jewish control, a veritable storm of indignation and anger has broken out in all the levels of the nation".[33] Prince Wilhelm called Stoecker "...the most powerful pillar, the bravest, most fearless fighter for Your Monarchy and Your Throne among the people!.... He has personally and alone won over 60, 000 workers for you and your power from the Jewish Progressives and Social Democrats in Berlin!...O dear Grandpa, it is disgusting to observe how in our Christian-German, good Prussian land, the Judenthum, twisting and corrupting everything, has the cheek to attack such men, and in the most shameless, insolent way to seek their downfall"."[33] Impressed with his grandson's arguments, the Emperor kept Stoecker on.[22] In November 1887, at a Christian Social event at the house of Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, Prince Wilhelm stood next to Stoecker, praised him as the "second Luther", declared his support for the CSP as bringing about the spiritual regeneration of Germany and urged men to vote for the CSP.[34]

Downfall

[edit]In 1888, when the Emperor Wilhelm died, Frederick succeeded to the throne, but as he was already dying of throat cancer, he did not dismiss Stocker as he had promised.[22] Bismarck threatened to resign if Stoecker were dismissed, but Frederick ordered that Stoecker was to avoid speaking on political matters in public.[22] After a reign of 99 days, Frederick died and was succeeded by his son, Wilhelm II, who kept Stoecker on as court chaplain. Stoecker had long attacked the National Liberal Party as a "Jewish" party, and in 1890, Wilhelm II was informed by the leaders of National Liberals that they would not vote for his bills in the Reichstag unless he were to sack Stoecker.[35] It was to win the support of the National Liberals, not objections to Stoecker's anti-Semitism, that caused Wilhelm II to dismiss Stoecker as court chaplain in 1890.[35] The Christian Social Party failed, as many of the younger and more radical völkisch leaders from the Mittelstand found Stoecker too tame, too Christian (some of the völkisch activists rejected Christianity and wanted to bring back the worship of the old gods) and too deferential to the Junkers, and some of the Christian Socials, led by Friedrich Naumann, broke away because of his anti-Semitism.[2]

Stoecker's position as court chaplain from 1874 to 1890 made him one of the most influential Lutheran clergymen of the entire 19th century, and in 1891, the theologian Reinhold Seeberg called Stoecker "the most powerful church leader for pastors".[20] After his death in 1909, Pastor Johannes Haussleiter wrote, "Nobody has so lastingly influenced the rising generation of pastors and has put his mark on them for decades to come as he did".[36] Stoecker's insistence that Jews were a race, not a religion, and that Jewish "racial traits" were so repulsive that no proper Christian could ever love a Jew and to love Christ was to hate Jews, had a major impact on the Lutheran church well into the 20th century, and helped to explain the Lutherans' support of the Nazi regime.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 108.

- ^ a b Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e f Levy, Richard "Our Demands on Modern Jewry" pp. 525–526 from Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1 edited by Richard Levy, Santa Monica: ABC-Clio, 2005 p. 525.

- ^ a b Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 pp. 95 & 109.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 109.

- ^ a b c d Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 110.

- ^ a b Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 111.

- ^ a b James, Pierre The Murderous Paradise: German Nationalism and the Holocaust, Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001 p. 160.

- ^ a b Levy, Richard "Our Demands on Modern Jewry" pp. 525–526 from Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1 edited by Richard Levy, Santa Monica: ABC-Clio, 2005 p. 526.

- ^ Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b c Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 101.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 104.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 105.

- ^ Röhl, John The Kaiser and his court : Wilhelm II and the government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 197.

- ^ James, Pierre The Murderous Paradise: German Nationalism and the Holocaust, Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001 p. 163.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 pp. 96.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 96.

- ^ a b Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 97.

- ^ a b c d Röhl, John The Kaiser and his court : Wilhelm II and the government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 p. 198.

- ^ a b c d e f Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 115.

- ^ a b c Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 113.

- ^ Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 114.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 p. 72.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 p. 73.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 pp. 73–74.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 p. 74.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 pp. 76–77.

- ^ Hartston, Barnet Peretz Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2005 p. 76.

- ^ a b Röhl, John The Kaiser and his court : Wilhelm II and the government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 p. 200.

- ^ Röhl, John The Kaiser and his court : Wilhelm II and the government of Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994 pp. 201–202

- ^ a b Green Harold "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue" pp. 106–129 from Politics and Policy, Volume 31, Issue # 1, March 2003 p. 116.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995p. 97.

- ^ Telman, Jeffrey "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian Mission" pp. 93–112 from Jewish History, Volume 9, Issue # 2. Fall 1995 p. 98.

Further reading

[edit]- Barnet Pertz Hartston (2005). Sensationalizing the Jewish Question: Anti-Semitic Trials and the Press in the Early German Empire. Leiden: Brill.

- Harold M. Green (2003). "Adolf Stoecker: Portrait of a Demagogue". Politics & Policy. 31 (1): 106–129.

- Richard Levy (2005). "Our Demands on Modern Jewry". Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. Santa Monica: ABC-Clio.

- D. A. Jeremy Telman (1995). "Adolf Stoecker: Anti-Semite with a Christian mission". Jewish History. 9 (2): 93–112. doi:10.1007/BF01668991. S2CID 162391831.

- Trosclair, Wade James, "Alfred von Waldersee, monarchist: his private life, public image, and the limits of his ambition, 1882–1891" (LSU Theses #2782 2012) online; includes coverage of Stoecker

External links

[edit]- 1835 births

- 1909 deaths

- People from Halberstadt

- Politicians from the Province of Saxony

- 19th-century German Lutheran clergy

- German Conservative Party politicians

- Christian Social Party (Germany) politicians

- Members of the 5th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 6th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 7th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 8th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 10th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 11th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the 12th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the Prussian House of Representatives

- German Christian socialists

- Lutheran socialists

- German chaplains

- Lutheran chaplains

- Antisemitism in Germany

- German people of the Franco-Prussian War