Pollux (star)

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Gemini |

| Pronunciation | /ˈpɒləks/[1] |

| Right ascension | 07h 45m 18.94987s[2] |

| Declination | +28° 01′ 34.3160″[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.14[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Red clump[4] |

| Spectral type | K0 III[5] |

| U−B color index | +0.86[3] |

| B−V color index | +1.00[3] |

| V−R color index | +0.75[3] |

| R−I color index | +0.50[3] |

| Variable type | Suspected[6] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +3.23[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −626.55 mas/yr[2] Dec.: −45.80 mas/yr[2] |

| Parallax (π) | 96.54 ± 0.27 mas[2] |

| Distance | 33.78 ± 0.09 ly (10.36 ± 0.03 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +1.08±0.02[8] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.91±0.09[9] M☉ |

| Radius | 9.06±0.03[10] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 32.7±1.6[10] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.685±0.09[11] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,586±57[10] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | –0.07 to +0.19[11] dex |

| Rotation | 660±15 d[12] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 2.8[13] km/s |

| Age | 1.19±0.3[9] (0.9 – 1.7)[4] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| ARICNS | data |

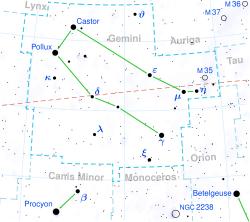

Pollux is the brightest star in the constellation of Gemini. It has the Bayer designation β Geminorum, which is Latinised to Beta Geminorum and abbreviated Beta Gem or β Gem. This is an orange-hued, evolved red giant located at a distance of 34 light-years, making it the closest red giant (and giant star) to the Sun. Since 1943, the spectrum of this star has served as one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.[15] In 2006 an exoplanet (designated Pollux b or β Geminorum b, later named Thestias) was announced to be orbiting it.[11]

Nomenclature

[edit]

β Geminorum (Latinised to Beta Geminorum) is the star's Bayer designation.

The traditional name Pollux refers to the twins Castor and Pollux in Greek and Roman mythology.[16] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[17] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016 included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN, which included Pollux for this star.[18]

Castor and Pollux are the two "heavenly twin" stars giving the constellation Gemini (Latin, 'the twins') its name. The stars, however, are quite different in detail. Castor is a complex sextuple system of hot, bluish-white type A stars and dim red dwarfs, while Pollux is a single, cooler yellow-orange giant. In Percy Shelley's 1818 poem Homer's Hymn to Castor and Pollux, the star is referred to as "... mild Pollux, void of blame."[19]

Originally the planet was designated Pollux b. In July 2014 the International Astronomical Union launched NameExoWorlds, a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[20] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[21] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning name was Thestias for this planet.[22] The winning name was based on that originally submitted by theSkyNet of Australia; namely Leda, Pollux's mother. At the request of the IAU, 'Thestias' (the patronym of Leda, a daughter of Thestius) was substituted. This was because 'Leda' was already attributed to an asteroid and to one of Jupiter's satellites.[23][24]

In the catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of al Achsasi al Mouakket, this star was designated Muekher al Dzira, which was translated into Latin as Posterior Brachii, meaning the end in the paw.[25]

In Chinese, 北河 (Běi Hé), meaning North River, refers to an asterism consisting of Pollux, ρ Geminorum, and Castor.[26] Consequently, Pollux itself is known as 北河三 (Běi Hé sān, English: the Third Star of North River.)[27]

Physical characteristics

[edit]

At an apparent visual magnitude of 1.14,[28] Pollux is the brightest star in its constellation, even brighter than its neighbor Castor (α Geminorum). Pollux is 6.7 degrees north of the ecliptic, presently too far north to be occulted by the Moon. The last lunar occultation visible from Earth was on 30 September 116 BCE from high southern latitudes.[29]

Parallax measurements by the Hipparcos astrometry satellite[30][31] place Pollux at a distance of about 33.78 light-years (10.36 parsecs) from the Sun.[2] This is close to the standard unit for determining a star's absolute magnitude (a star's apparent magnitude as viewed from 10 parsecs). Hence, Pollux's apparent and absolute magnitudes are quite close.[32]

The star is larger than the Sun, with about two[9] times its mass and almost nine times its radius.[11] Once an A-type main-sequence star similar to Sirius,[33] Pollux has exhausted the hydrogen at its core and evolved into a giant star with a stellar classification of K0 III.[5] The effective temperature of this star's outer envelope is about 4,666 K,[11] which lies in the range that produces the characteristic orange hue of K-type stars.[34] Pollux has a projected rotational velocity of 2.8 km·s−1.[13] The abundance of elements other than hydrogen and helium, what astronomers term the star's metallicity, is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 85% to 155% of the Sun's abundance.[11][35]

An old estimate for Pollux's diameter obtained in 1925 by John Stanley Plaskett via interferometry was 13 million miles (20.9 million km, or 18.5 R☉), significantly larger than modern estimates.[36] A more recent measurement by the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer give a radius of 9.06 R☉.[10] Another estimate that uses Pollux's spectral lines obtained 8.9 R☉.[37]

Evidence for a low level of magnetic activity came from the detection of weak X-ray emission using the ROSAT orbiting telescope. The X-ray emission from this star is about 1027 erg s−1, which is roughly the same as the X-ray emission from the Sun. A magnetic field with a strength below 1 gauss has since been confirmed on the surface of Pollux; one of the weakest fields ever detected on a star. The presence of this field suggests that Pollux was once an Ap star with a much stronger magnetic field.[33] The star displays small amplitude radial velocity variations, but is not photometrically variable.[38]

Planetary system

[edit]Since 1993 scientists have suspected an exoplanet orbiting Pollux,[39] from measured radial velocity oscillations. The existence of the planet, Pollux b, was confirmed and announced on June 16, 2006. Pollux b is calculated to have a mass at least 2.3 times that of Jupiter. The planet is orbiting Pollux with a period of about 590 days.[11]

The existence of Pollux b has been disputed; the possibility that the observed radial velocity variations are caused by stellar magnetic activity cannot be ruled out.[12]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (Thestias) (disputed[12]) | > 2.30±0.45 MJ | 1.64±0.27 | 589.64±0.81 | 0.02±0.03 | — | — |

References

[edit]- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006), A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub, ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ a b c d e van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 474 (2): 653–664, arXiv:0708.1752, Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, S2CID 18759600

- ^ a b c d e Ducati, J. R. (2002), "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system", CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues, 2237: 0, Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D, doi:10.26093/cds/vizier, VizieR Cat. II/237/colors.

- ^ a b Howes, Louise M.; Lindegren, Lennart; Feltzing, Sofia; Church, Ross P.; Bensby, Thomas (April 23, 2018), "Estimating stellar ages and metallicities from parallaxes and broadband photometry - successes and shortcomings", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 622: A27, arXiv:1804.08321, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833280, ISSN 0004-6361

- ^ a b Morgan, W. W.; Keenan, P. C. (1973), "Spectral Classification", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 11: 29–50, Bibcode:1973ARA&A..11...29M, doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.11.090173.000333

- ^ Petit, M. (October 1990), "Catalogue des étoiles variables ou suspectes dans le voisinage du Soleil", Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement (in French), 85 (2): 971, Bibcode:1990A&AS...85..971P.

- ^ Famaey, B.; et al. (January 2005), "Local kinematics of K and M giants from CORAVEL/Hipparcos/Tycho-2 data. Revisiting the concept of superclusters", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 430 (1): 165–186, arXiv:astro-ph/0409579, Bibcode:2005A&A...430..165F, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041272, S2CID 17804304

- ^ Carney, Bruce W.; et al. (March 2008), "Rotation and Macroturbulence in Metal-Poor Field Red Giant and Red Horizontal Branch Stars", The Astronomical Journal, 135 (3): 892–906, arXiv:0711.4984, Bibcode:2008AJ....135..892C, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/892, S2CID 2756572

- ^ a b c Hatzes, A. P.; et al. (July 2012), "The mass of the planet-hosting giant star β Geminorum determined from its p-mode oscillation spectrum", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 543: 9, arXiv:1205.5889, Bibcode:2012A&A...543A..98H, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219332, S2CID 53685387, A98.

- ^ a b c d Baines, Ellyn K.; Armstrong, J. Thomas; Schmitt, Henrique R.; Zavala, R. T.; Benson, James A.; Hutter, Donald J.; Tycner, Christopher; van Belle, Gerard T. (2017). "Fundamental parameters of 87 stars from the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (1): 16. arXiv:1712.08109. Bibcode:2018AJ....155...30B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa9d8b. S2CID 119427037.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hatzes, A. P.; et al. (2006), "Confirmation of the planet hypothesis for the long-period radial velocity variations of β Geminorum", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 457 (1): 335–341, arXiv:astro-ph/0606517, Bibcode:2006A&A...457..335H, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065445, S2CID 14319327

- ^ a b c Aurière, M.; Petit, P.; et al. (February 2021), "Pollux: A weak dynamo-driven dipolar magnetic field and implications for its probable planet", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 646: A130, arXiv:2101.02016, Bibcode:2021A&A...646A.130A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039573

- ^ a b Massarotti, Alessandro; et al. (January 2008), "Rotational and Radial Velocities for a Sample of 761 HIPPARCOS Giants and the Role of Binarity", The Astronomical Journal, 135 (1): 209–231, Bibcode:2008AJ....135..209M, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/1/209, S2CID 121883397

- ^ "POLLUX -- Variable Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2012-01-14

- ^ Garrison, R. F. (December 1993), "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 25: 1319, Bibcode:1993AAS...183.1710G, archived from the original on 2019-06-25, retrieved 2012-02-04

- ^ "Pollux", STARS, University of Illinois, Urbana–Champaign Campus, 2008, retrieved 2009-05-29.

- ^ IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN), retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1 (PDF), retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Homer's Hymn To Castor And Pollux by Percy Bysshe Shelley", allpoetry.com, retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars", NameExoWorlds, IAU, 9 July 2014, retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ "NameExoWorlds", nameexoworlds.iau.org, archived from the original on 15 August 2015, retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released", NameExoworlds, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015, retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ "NameExoWorlds", nameexoworlds.iau.org, archived from the original on 1 February 2018, retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "YOU helped name an exoplanet!", TheSkyNet, 2015-12-17, archived from the original on 2018-05-07, retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ Knobel, E. B. (June 1895), "Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 55 (8): 429–438, Bibcode:1895MNRAS..55..429K, doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429.

- ^ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 Archived 2011-01-30 at the Wayback Machine, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ^ Lee, T. A. (October 1970), "Photometry of high-luminosity M-type stars", Astrophysical Journal, 162: 217, Bibcode:1970ApJ...162..217L, doi:10.1086/150648

- ^ Meeus, Jean (1997), Mathematical Astronomy Morsels (1st ed.), Richmond, Virginia: Willmann-Bell, ISBN 978-0-943396-51-4.

- ^ Perryman, M. A. C.; Lindegren, L.; Kovalevsky, J.; et al. (July 1997), "The Hipparcos Catalogue", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 323: L49–L52, Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P

- ^ Perryman, Michael (2010), "The Making of History's Greatest Star Map", Astronomers' Universe, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, Bibcode:2010mhgs.book.....P, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11602-5, ISBN 978-3-642-11601-8

- ^ "The Brightest Stars". 2013-02-18. Archived from the original on 2013-02-18. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ a b Aurière, M.; et al. (September 2009), "Discovery of a weak magnetic field in the photosphere of the single giant Pollux", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 504 (1): 231–237, arXiv:0907.1423, Bibcode:2009A&A...504..231A, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912050, S2CID 14295272

- ^ "The Colour of Stars", Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, December 21, 2004, archived from the original on March 18, 2012, retrieved 2012-01-16

- ^ The abundance is determined by taking the value of [Fe/H] in the table to the power of 10. Hence, 10−0.07 = 0.85 while 10+0.19 = 1.55.

- ^ Plaskett, J. S. (1922). "The Dimensions of the Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 34 (198): 79–93. Bibcode:1922PASP...34...79P. doi:10.1086/123157. ISSN 0004-6280. JSTOR 40668597.

- ^ Gray, David F.; Kaur, Taranpreet (2019-09-10). "A Recipe for Finding Stellar Radii, Temperatures, Surface Gravities, Metallicities, and Masses Using Spectral Lines". The Astrophysical Journal. 882 (2): 148. Bibcode:2019ApJ...882..148G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab2fce. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Henry, Gregory W.; et al. (September 2000), "Photometric Variability in a Sample of 187 G and K Giants", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 130 (1): 201–225, Bibcode:2000ApJS..130..201H, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.40.8526, doi:10.1086/317346, S2CID 17160805.

- ^ A. P. Hatzes; et al. (1993), "Long-period radial velocity variations in three K giants", The Astrophysical Journal, 413: 339–348, Bibcode:1993ApJ...413..339H, doi:10.1086/173002.

External links

[edit]- "Notes for star HD 62509". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- "Pollux". SolStation. Retrieved 2005-11-21.

- Sabine Reffert; et al. (2006-07-07). "Precise Radial Velocities of Giant Stars II. Pollux and its Planetary Companion". Astrophys. J. 652 (1): 661–665. arXiv:astro-ph/0607136. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..661R. doi:10.1086/507516. S2CID 18252884.